Ken Williams: An excerpt from The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games interview

It’s only fitting that we finish our four-part exploration of The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games with a focus on one half of the husband and wife team that helped pioneer the graphic adventure in the first place. Without Ken and Roberta Williams, perhaps Bitmap Books’ delightful coffee table hardcover would be a thinner text-only paperback instead. The following excerpt from Bitmap’s conversation with Sierra’s legendary co-founder (reprinted with permission) is one of more than 50 such interviews contained within its 500 pages. Not included in its original publication, this interview is just one small addition to the second edition printing, which is due out August 10th. And did we mention it’s got pictures, too? Lots and lots of glorious pictures!

Ken Williams

Ken Williams is a man who needs few words of introduction to fans of classic point-and-click adventure games, being one half of the duo that founded legendary publisher Sierra On-Line, alongside his wife, Roberta Williams, the creator and designer of the best-selling and hugely popular King’s Quest series.

Ken Williams is a man who needs few words of introduction to fans of classic point-and-click adventure games, being one half of the duo that founded legendary publisher Sierra On-Line, alongside his wife, Roberta Williams, the creator and designer of the best-selling and hugely popular King’s Quest series.

Can you recall how you developed an interest in computing, and how this led to the idea of using them as a platform for interactive storytelling?

Back when I was a junior in high school, we had a field trip to visit UCLA, the university in Los Angeles. This would have been 1970, and the big mainframe computers were all that existed because home computers hadn’t been invented yet. At UCLA, we toured a computer lab, and I was able to play a simple text game on a teletype machine. It was love at first sight...

Who took more of an interest in computer gaming at the time, yourself or Roberta?

At the time Sierra started, I envisioned it as a Microsoft-style company. I was working on a Fortran compiler for the TRS-80. Roberta was the one who had the idea of doing games. She bought me an Apple II computer for Christmas of 1979 and insisted that I write some code for the adventure game she designed.

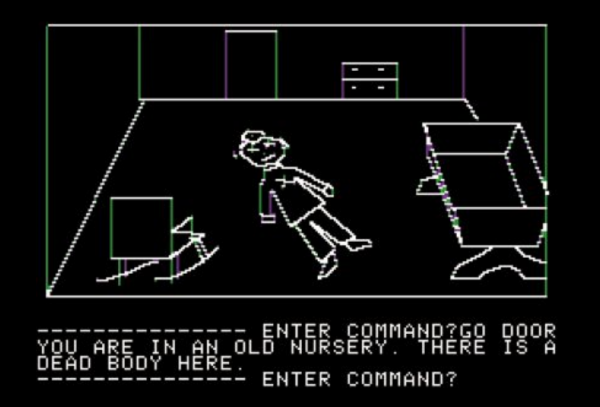

That title was Mystery House, the first computer adventure game to feature an (albeit simplistic) graphical element, designed by Roberta. Do you recall how this game and its pioneering graphics came about, and was it hard to achieve on the memory- limited floppy disk format of the time?

When we started, floppy disks had only 80k of storage. Roberta was the one who wanted graphics and kept insisting on doing a game with graphics. I told her it was impossible, but she can be very stubborn... I then had the idea of producing graphics by using vector graphics and storing the game logic as a series of simple tables. Mystery House, the entire game, fit on a single 80k floppy!

Was the success of Mystery House – which went on to sell 80,000 copies worldwide – a surprise to you, and how much did the game and Roberta’s creativity contribute to the establishment of Sierra as such a prolific publisher of graphic adventure software?

Roberta deserves all the credit for founding Sierra and really for constantly ‘changing up’ the definition of the graphic adventure game. She always insisted that each of her games would evolve the genre in some way…

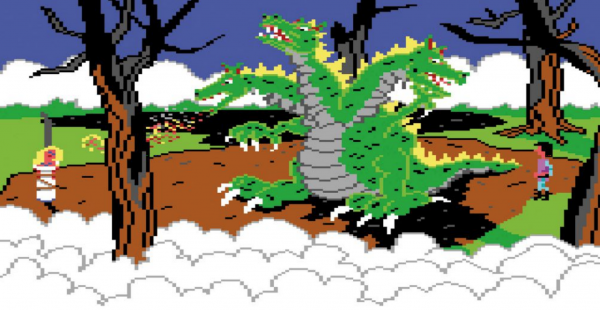

What are your recollections on the origin of the original King’s Quest, and how instrumental was the fact that a major company like IBM approached you to help finance the development of the game?

King’s Quest was one hundred per cent Roberta’s creation. She came up with the idea by melding the big-picture concepts of Disney-style entertainment and nursery rhymes. Roberta wanted a series that children would enjoy but that would also entertain adults. It was meant to be something that families could play together.

The IBM deal is a very long story. Sierra had diversified into video game consoles at a time when the bottom fell out of the console market. We got caught with a heavy investment in video game cartridges that would not sell. This was around the time when Atari famously had to bury thousands of E.T. cartridges in the desert. The company came very close to bankruptcy. I approached IBM and talked them into funding some games. We used their money to fund King’s Quest 1, and it saved the company. King’s Quest was the first adventure game to utilise IBM’s new EGA graphics card and introduce an animated on-screen protagonist who could move around an environment behind and in front of background objects.

Do you feel lucky for recruiting people like Jim Walls (Police Quest), Al Lowe (Leisure Suit Larry) and others, who hadn’t necessarily had any game design experience but who you were able to train to produce their own successful game franchises?

I was very lucky! Sierra had an amazing team of designers, coders, artists, musicians… everything. Because we were the top game company at the time, we were able to attract the most talented people in the industry. Sierra was very fortunate to have a truly amazing team of developers.

Jane Jensen has stated how you believed in artistic freedom for all of your designers, with minimal management interference. Was this important to your company ethos?

Absolutely… I used to always say that great novels are written by a single person. I wanted the game players to feel a one-to-one connection to the person who wrote the game. I didn’t want their creative vision muddied by having everyone on the team kicking in ideas. It was a constant battle to stop anyone interfering with the designers.

Sierra’s journey was one of constant technical innovation – from some of the first adventure games to use animated on-screen characters, sound cards, voice acting, CD-ROM and the motion capture of actors, up to the Disney-like animated spectacle of later games such as King’s Quest VII. How important was it to push the envelope with regard to technology?

At Sierra, I thought it was everything. I always had a philosophy that there are two kinds of companies: those that lead and those that follow. I saw Sierra as a leader and that it was our job to show the industry where to go. My time at Sierra spanned eighteen years, and the level of art changed dramatically during that time. Our goal was always to push the envelope in art, animation, music and sound effects. That meant something completely different when we started out in 1979 than it did in 1996, and it means something very different today. When Sierra started, computers had no ability to do colour, and, even if the hardware could have done more, the lack of memory and limited storage on floppies made doing anything virtually impossible. Another huge constraint was the lack of utilities. It’s tough to believe today, but there were no paint programs, no animation programs. It was the Wild West of software development, with nothing but pioneering to be done.

A top priority at Sierra, and a competitive advantage for us, was our focus on developing tools that allowed designers, artists and musicians to do their jobs. Much of what made Sierra special was that we were always on the cutting edge of visuals and sound.

Did you view other adventure publishers like Lucasfilm as healthy competition, and did their releases – like The Secret of Monkey Island and the Indiana Jones adventure series – spur you on to create better games?

Absolutely. I constantly worried about the competition, and we had some incredible competitors back then. That said, I used to do everything possible to avoid having our people look at competitor’s products. It is a sucker trap to look at other people’s products and then try to replicate them. Sierra’s job was to lead, not follow.

Looking back, which of Sierra’s adventure games are you particularly proud of?

I loved them all. It’s like asking someone which of their children they loved the most. It’s an impossible comparison. Every game we did tried to have a particular ‘mission’. I always subscribed to the theory of ‘business as war’. Each game had some reason to exist. I was trying to enter a category or leverage a technology, or, in some way, capture turf. The things I’m proudest of are probably The Sierra Network, where we leveraged our adventure game technology (SCI) into a whole new category of game. And also some of the games people have forgotten that were incredible at the time – like The Castle of Dr. Brain.

Is it heartwarming to know that Sierra’s adventures, characters and experiences you created nearly four decades ago – from the King’s Quest series to Space Quest, Gabriel Knight, Leisure Suit Larry and others – not only built a huge fanbase around the world at the time but still hold a special place in classic adventure gamer’s hearts?

It is shocking to Roberta and me that people remember us nearly 25 years after we retired. Sometimes we are honoured, and sometimes we are embarrassed. Overall, we just think it is really great. The sad thing is that Sierra doesn’t still exist. I always used to say that my goal was to build a Sierra that would still be around for my grandchildren, and that didn’t happen. It was such an incredibly sad ending to a great company that I still think about it almost every day. Just horrible; especially what happened to all the incredible people who built such great products and then had their dreams ruined. It’s so sad to think about.

Note: As an affiliate partner, Adventure Gamers gets a small percentage of proceeds from every copy of The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games sold through our links. Because the genre is far from done yet. Long live the adventure, pre-order your own copy from Bitmap Books for more!