Agustín Cordes interview

Agustín Cordes seems to like making people suffer. First he scared the pants off us with his debut horror adventure Scratches, and now the agonizing wait for his his highly-anticipated next game, Asylum, is taking much longer than expected. But that won't stop us from learning everything we can in the meantime. With Asylum getting renewed attention on Steam Greenlight at the moment, we decided the time was right to find out all there is to know about Asylum and the man behind the madness. Naturally, we couldn't resist talking about Scratches as well, and even get a sneak preview of Agustín's surprising future plans.

Ingmar Böke: Hi Agustín, it's a pleasure to welcome you to Adventure Gamers. Like many adventure game developers, you started as a devout genre fan before becoming a designer yourself. Take us back in time and tell us how you got "infected" with the adventure game virus in earlier days.

Agustín Cordes: Hi Ingmar, on the contrary, it’s my pleasure to be here! Well, not “here” per se, but… you know what I mean. I’ve just parked my time machine in the backyard and can confirm that I was infected with the adventure game disease in 1988 while playing King’s Quest. You see, I was quite the video games freak back then, going crazy over stuff like Zaxxon, Space Invaders, Digger and Jumpman, but King’s Quest was without doubt the most sublime experience of my childhood. It really changed forever my whole perception of games and stimulated my imagination in a way only the best books ever did.

The most immediately revealing aspect was the possibilities it offered. Jumpman and similar games were a hoot; they had clear goals, advancing levels was fun and that was enough for me. But King’s Quest… The first thought that came to mind was “oh wow, I can go ANYWHERE I want to?” And you can bet that was the case. Just getting lost in Daventry with unknown dangers and mysteries lurking around the corner, anticipating the next encounter with friend or foe, was a turning point in my life. Yes, I’m that serious about it. I quickly realized that this is what I wanted to do eventually: make games, the adventure genre being the ideal format for me. I loved the possibilities it offered, the way you could introduce a storyline to the players and somehow play along with them. Of course, this was just the beginning and I’ve played hundreds of adventures ever since, but King’s Quest remains that revelatory experience.

Ingmar: Was there a key moment since then that gave you direction in the kind of developer you wanted to be? I heard that Dark Fall was a very important game for you. Is that game responsible for the "next step"?

|

Agustín Cordes and Ingmar Böke |

Agustín: Yes, I’d say the key moment that made me jump ship can be traced back to Dark Fall. I’d always wanted to create an adventure ever since playing King’s Quest, and in fact the Scratches idea was already roaming inside my head for quite some time, but Dark Fall was the inflection point. I mean, that was essentially a one man project rivalling the greatest productions at the moment! I was floored; the possibilities introduced by Dark Fall for a wannabe developer like me were overwhelming: a full-blown, lengthy adventure with a very polished look and yet minimal investment (other than time and lots of sweat, of course). Sure, it wasn’t the first indie game ever, but in my mind it remains the most significant indie game. I don’t think Dark Fall gets all the credit it deserves these days: we’re talking about a groundbreaking title, a classic by now, when the term “indie gaming” wasn’t even common in the industry. It made me feel so confident about the idea of making games that I began to put wheels in motion to do Scratches.

I maintained lots of correspondence with Jonathan Boakes, who was extremely helpful at the time and provided much insightful advice. I like to think that I have returned the favor to other developers over the years. Dark Fall wasn’t a revelation only in terms of possibilities, but also a first glimpse into the most helpful and kindest community in the industry.

Ingmar: Not everyone may know that you worked as a journalist for a big adventure game website for a while. I'd be interested in hearing your memories of that experience.

Agustín: It’s a rather nice story how it all began, if a bit embarrassing. It was early in 2002 and I had been lurking around many adventure game forums for who knows how long. I sure can’t remember by now. Syberia was just being released and many websites began to claim that it was the adventure renaissance all fans were expecting. Well, not me because I was convinced Syberia was a pile of stinking rubbish (I still do, mind you) and decided to do what any self-respecting internet dweller would do: rant about it. So I decided that Just Adventure+ should be my battleground and posted what is possibly the most vicious rant about Syberia that exists on the web. It’s still fondly recalled among the old timers from the forum as the first flamewar at JA+. That was probably my first post ever and I was already making myself some mortal enemies. Gotta love them internets!

Things cooled down eventually and I became very tied to that community. So one day I approached Randy Sluganski, who owned JA+ at the time, and asked if he’d be interested in publishing an article of mine. This was a piece I had been working on for some time about unfinished adventures (although strictly speaking it featured Meantime, an RPG). Randy loved it and was very happy to publish it. Readers liked it too, and that’s how it became a hobby for me. The next piece was about the unfortunate Zelenhgorm, then Runaway (the first English review ever, actually!), and so on. I mostly focused on rare stuff, or Spanish games not yet available in English. It was a wonderful period, and it’s safe to say it helped me to carve my small spot in this industry. Randy, who passed away recently, was a true mentor back then, always encouraging me to write, endorsing my work, and ultimately becoming an immense help during the development of Scratches. I remember him fondly as one of the very first friends I made on the internet.

Ingmar: Scratches sold around 250,000 copies and won lots of awards. In a way, it must have been quite a nightmare to create this game, as it was your first game and you had a tiny team. Guide us through the development of Scratches and tell us about the pros and cons of this intense journey.

|

Scratches |

Agustín: It was a nightmare alright, but not without its share of exciting moments. At first it was supposed to be a hobby of sorts. I mean, I always was serious about doing a quality adventure, but I had another job at the time and wasn’t quite ready to take that “leap of faith”, so for some time Scratches was a secondary thing for me. However, when we released the first playable teaser in Halloween 2003, the reaction floored me. People loved the thing even though it was extremely short and were very supportive of the project.

Then, once we began to get contacted by publishers, I decided to take the plunge and quit my job. Scratches became a very serious goal and that’s why we decided to up the ante. We went from a simple slideshow engine to the atmospheric panorama style present in the final game, while retaining the visual effects seen in the teaser (rain and thunderstorm). A whole new floor was added to the Blackwood mansion and loads of things were tweaked. All the work of several months that we did for the teaser was essentially scrapped (graphics were deemed not worthy of the new look and the engine was completely rewritten).

The new format and style were reintroduced in the so-called Second Teaser in July 2004, including the “passing clouds” effect that would be later present in the full game, a first in panorama adventures. For some reason that still escapes me today, reception among adventure fans was colder this time, even though the new teaser was a decidedly huge boost in quality. However, it did get more attention generally.

That was basically the whole inception and for the remaining two years or so my entire life circled around Scratches. In retrospect, it was an insanely ambitious project. We should have begun with something smaller, but while there were other ideas, the concept for Scratches was the most well developed one. It was crazy to make our own engine as well but there was nothing quite suitable at the time. Keep in mind that we were essentially two persons working on this thing besides the music composer in Croatia. On top of that, it was a conscious decision to sign with several publishers as opposed to one big deal to minimize risks. As the game neared completion, we were dealing with almost a dozen companies each with different expectations and deadlines.

“Intense journey” is a nice way to put it. It was very rough at times and the only thing that kept us going was the support from the community. You’d think I'd have learned not to engage overly ambitious projects without the resources but, alas, fate decided that wouldn’t be the case…

Ingmar: When looking back at Scratches, what did and didn't work as well as you'd hoped?

Agustín: Technically speaking, the engine (SCream) wasn’t stable at first. I have to admit the game was rushed out and I’m still kicking myself for that as it exhibited a recurring crash that was fixed after very few extra days of polishing. Performance was fairly slow when moving between the nodes; the engine wasn’t very advanced so there was no caching and each node was being loaded on demand, which resulted in an often excruciating pace. Also, the interface felt rather clunky (and we’re still trying to get it right for panoramic adventures).

Design-wise, it was a dense game. My intention was always to mimic the feel of reading an H.P. Lovecraft story, but it was overdone. The game was divided into three days and the first one was many hours of introduction and exposition. Nothing noteworthy happened, and as a result many players were bored. Some of the puzzles during this stage of the game were forced as well, as the intention was to provide plenty of freedom to explore the house but at the same time make sure players saw specific things.

It was all part of a plan though: the central mystery was fully introduced in the second day when things began to pick up. This gave players a clear sense of purpose and the tools to piece together all the disjointed clues they experienced on the first day. The change in mood helped a lot as well: from sad, evocative music during the first day, we went to a very suggestive composition hinting at dark secrets; from a clear day to a sinister thunderstorm, and all this after experiencing a terrifying first night. Players have consistently told us that they got irremediably hooked from this point on, so I guess it was effective in the end, even though the actual plot was kickstarted one-third into the game.

It was all part of a plan though: the central mystery was fully introduced in the second day when things began to pick up. This gave players a clear sense of purpose and the tools to piece together all the disjointed clues they experienced on the first day. The change in mood helped a lot as well: from sad, evocative music during the first day, we went to a very suggestive composition hinting at dark secrets; from a clear day to a sinister thunderstorm, and all this after experiencing a terrifying first night. Players have consistently told us that they got irremediably hooked from this point on, so I guess it was effective in the end, even though the actual plot was kickstarted one-third into the game.

I still like how all of this worked out and would never change the design of the game. These shifts in mood and slow pace at which the events unfolded, introducing the notion of time passing by and sense of belonging in the Blackwood house, gave players a greater sense of immersion; by the time the third and final day arrived they had this feeling of impending doom and anticipated the conclusion of the story, while at the same time feeling sorry everything was coming to an end. As much as they were afraid of the mansion, they were just as saddened to leave it behind. I believe this sort of mixed emotions about the story is perhaps the most singular feature of Scratches. Many told me later how they had grown attached to the Blackwood estate, feeling decidedly disturbed upon revisiting the vandalized location in the Director’s Cut edition.

So, I’d say the overall balance was positive. Certainly, some players hated the game and that’s fine, but others still have the story embedded in their minds and that’s more than enough for me.

Ingmar: Since your next game, Risk Profile, was never released in English, many people may not even be aware of its existence. What can you tell us about that game?

|

Risk Profile |

Agustín: This was an interesting project that came to our attention shortly before Scratches Director's Cut was completed. The concept was rather weird, given it was an educational game envisioned by our Argentinian taxation office that was supposed to teach children how to… well, pay taxes. But the thing that most surprised me upon reviewing the specifications of the project was that they were aiming to do this under the guise of a point-and-click adventure, even citing classic examples such as Monkey Island and Broken Sword. It was an unlikely origin for an adventure (I mean taxes, of all things!) but the team behind the concept was very passionate about the subject and had very intriguing ideas in mind.

It wasn’t only about taxes though; the game had to educate children about how they can be good citizens (such as helping people, keeping the streets clean, reporting crimes, etc.). The draft design included mini-games and optional quests giving points so that players would be able to compare their performance with global online rankings. The idea seemed very stimulating for kids but it was a demanding specification: the game had to be completed in 12 months and they expected 12 missions with about 3-4 unique scenes and characters for each, so it was a lot of content.

Even though the scope of the project was intimidating, we decided to give it a go as it was poised to be a one-of-a-kind experience. Plus, they were inclined to give us plenty of freedom with the script as long as we covered all the educational aspects. In the end it was a fun but stressful ride: the game was completed in 18 months with much pressure (remember we were spending public money with this), and I believe it was the first time in any country that a project of this sort was ever attempted.

It was definitely worth it though: kids loved the game; many are still hoping for a sequel today, and the resulting script was quite crazy and featured a twisted sense of humour. For example, at one point in the game you need information from a street bum who won’t say a thing unless you give him a beer, but you can’t give him actual beer with alcohol (you know, educational game for kids). So what you do is get a half-empty box of cereal and use the exhaust pipe of a defective car to mix it with motor oil, resulting in a disgusting beverage… which the bum loves. Later in the game, a news programme reports that giant creatures are wreaking havoc in the city while you see one slimy green tentacle grabbing a building. I still can’t believe they let me get away with all that stuff.

Ingmar: The obvious follow-up question: Is there a chance that Risk Profile will ever be released in English? Maybe this is a good opportunity for a shout out to potential translators.

Agustín: Unlikely, and I’m not even sure of the current situation with the legal rights of the game. The taxation office switched directors and they kind of disowned the game, so it got embroiled in disgusting political schemes. It’s truly a shame but there’s not much any of us can do about it right now. Any translation would have to be unofficial… and keep in mind that many jokes are very related to our culture, so much of the fun factor would probably be lost in translation, not to mention the educational angle that no one would care about. Still, I guess there’s no harm in asking if there’s enough interest.

Agustín: Unlikely, and I’m not even sure of the current situation with the legal rights of the game. The taxation office switched directors and they kind of disowned the game, so it got embroiled in disgusting political schemes. It’s truly a shame but there’s not much any of us can do about it right now. Any translation would have to be unofficial… and keep in mind that many jokes are very related to our culture, so much of the fun factor would probably be lost in translation, not to mention the educational angle that no one would care about. Still, I guess there’s no harm in asking if there’s enough interest.

Ingmar: Why did you and your former partner Alejandro Graziani decide to close the doors of Nucleosys after a very successful time together?

Agustín: After Risk Profile, it felt like Nucleosys was at the end of a cycle. Like I said, that game was a nightmare to produce and it’s under such stressful situations that both creative and management differences become more apparent. It just wasn’t working anymore between the two of us as partners, and the timing was appropriate with both Scratches DC and Risk Profile wrapped up. So the decision was made to go on different paths and call it a day for Nucleosys as a company.

Ingmar: Fortunately, the end of Nucleosys didn't mean the end of your career as a developer. In fact, it didn't take long before you came up with a new company, Senscape.

Agustín: Senscape was a fresh start indeed. Once Risk Profile was done for good, I badly wanted to return to personal projects and Asylum was the obvious next step. Risk Profile was an immensely valuable experience, allowing me to learn how to tackle a more ambitious project and lead a larger team. Some of the same folks that worked on that game joined Senscape and we immediately began work on Asylum. I wish I could say at this point that the “rest is history”, but no… we’re still dealing with the part about making history. <grin>

|

Ingmar, Achim Heidelauf, Agustin and Pablo Forsolloza at gamescom 2012 |

The original team was comprised by Pablo Forsolloza, basically the architect of the Hanwell Mental Institute; Juan Caratino, who mostly took care of characters and their animations – both of them extremely talented 3D artists; and Pablo Palomeque, who did concept art and some 2D artwork appearing in the game. I know you like the Argentinian movie The Secret In Their Eyes very much; well, Palomeque was involved in that movie doing matte paintings. He’s becoming quite the celebrity in the local industry! Anyway, right now the team is just Pablo and me, but I’m hoping to bring more talent to the project soon.

The same values that were present in Nucleosys also apply to Senscape: we love adventures and we’ll do everything in our power to support the genre. We love our fans, we listen to them, we always stay in touch and want them to feel like they’re part of the company. The worst aspect of leaving Nucleosys by far was dismantling the terrific community we had there… For a long time those forums were very active, always filled with great folks and exciting discussions taking place (and no flamewars!). I’m happy to see that we’re slowly getting to that point at Senscape; I mean, having a community of our own. So you could say that Senscape is not just about making games but also the people that play them.

Ingmar: You developed Scratches in your own bedroom. How has your way of working changed since then?

|

Agustin's home studio for Scratches (he's right; it's a little untidy) |

Agustín: Well, I have my own studio now and it’s much tidier than my old bedroom, so I guess that’s an improvement. Things have changed certainly, and I’ve learned from many mistakes in the past. For example, the Scratches script was completed halfway through its development, but in the case of Asylum it’s the first thing I did: a 55-page document written in the form of a short story which I gave to every team member, and we wouldn’t do any production until it was fully assimilated by everybody. All in all, things are more organized, although our approach to development remains very informal.

Ingmar: Asylum is currently on track for release in 2013, but originally it was scheduled to be launched quite a while ago. What has taken so long? You haven't spent the last few years playing video games instead of creating them, have you?

Agustín: Hell, no. I wish I could dedicate more time to games, actually. Most of my gaming these days is done in small bursts with mobile titles as I find the time. It’s been quite a while since I’ve been able to lock myself into playing a larger game for several hours.

Thing is, the problem with Asylum was that it was announced too early. Fans had been craving a follow-up to Scratches for too long and the intermezzo with Risk Profile didn’t help, so I decided to lift the veil of secrecy and announce the project. Originally it was set to be released in late 2011 and was announced in mid-2010, so the time to build up hype seemed appropriate enough. But we’re a small team without a proper budget, which means no tight schedule, and yes, development has been much slower than expected.

|

Agustin tells us he's working hard on Asylum.... but, wait, is this really why it's taking so long? |

There’s not much else to say, really; the project was never put on hold and we’ve been working non-stop on it for over four years now. Put simply: it’s a monster of an adventure that’s taking way too long to complete. But it’s not like we’re in a tough situation and the game is at risk; the entire asylum is graphically complete and can be fully explored, most assets we need are prepared, the engine is in a very mature state, the script has been ready for a while… What basically remains is implementing the game logic, which includes interaction with characters, doing many cutscenes, then polish, tweak, improve, polish, etc. It’s still going to take a while, but we’re definitely getting there.

So there you have it: we were pressured to announce the game, now we’re pressured to get it done. We’ll never have rest…

Ingmar: Speaking of Asylum, let’s talk about the story and setting of the game.

Agustín: It’s a horror adventure set in a mental asylum. Next question, please.

I wish that was all I could say about it, honestly. I love keeping things under wraps, always maintaining a sense of mystery, but it’s not possible these days. In fact, I believe there’s too much information already between teasers, trailers, previews and interviews such as this. Fortunately, we’ve been able to keep the details of the story locked inside a tight box (it probably helps that you can count with the fingers on both your hands the number of people who have read the script, unless you’re a mutant and have more than one hand, or more than ten fingers in total).

Anyway, all I’m going to say for now is that you’re an ex-patient of the Hanwell Mental Institute experiencing bizarre hallucinations. You can’t be sure whether they’re echoing actual events that took place during your stay in the asylum or you’re gradually losing your mind. The memories you have of that period are fuzzy and it’s evident you’re subconsciously repressing disturbing thoughts.

|

Still slaving away on... oh, never mind. |

It’s been many years since the institute was shut down after a notorious scandal, so believing it’s still abandoned you drive one afternoon to the lone structure sitting atop a cliff, determined to find out the truth about your past and the meaning behind these hallucinations. As it should be evident by now, the asylum is no longer abandoned, and the mystery is far more complicated than it seems…

That’s basically the setup. We keep hearing people asking for more details but that’s about all we’re going to say at least until the (full) demo is released. The less you know about the story before you play the game, the better the payoff.

As for the setting, if you love to explore old, decaying buildings, then Asylum will be the game of your dreams. We’ve heard from people that practice “urban exploring” but don’t play any games and they’re still looking forward to trying Asylum. What these people do is find abandoned buildings, often set to be demolished, and explore the hell out of them (which is dangerous and basically means trespassing on private property, so it’s my duty as a responsible game developer to tell you that is not legal). This is what you can do with the Hanwell Institute if you disregard the story and every game mechanic: just dedicate many hours’ worth of virtual touring around the place. The building was modelled with real blueprints of vintage asylums in mind and we were careful to make sure the architecture was as “correct” as possible, so it could well be a faithful reproduction of an actual asylum. It’s been designed and created with the same love and passion as the Blackwood manor.

So that’s another reason why the game is taking so darned long: our dedication to the Hanwell Institute is bordering on obsessive with every room (around one hundred!) brimming with details, backstory and stuff to investigate.

Ingmar: We know two people already from your viral marketing videos. Tell us about them and some of the other characters.

Agustín: Bertrand is the poor guy being interrogated by a man called Ellis Hawthorne, who unfortunately you will get to know very well during the game. Bertrand is a shy and sad kind of person, maybe someone you would call an emo these days if he constantly wore black and listened to The Cure all the time (no, he doesn’t).

Lenny is the closest thing you have to a friend in the Hanwell Institute. He’s kind, a bit dumb but a good soul nonetheless. You won’t remember him at first, but over the course of the adventure memories will resurface and you’ll learn a lot about Lenny and what he’s got to do with your past.

We have around ten characters in the game, of which you get to interact with four in the present. There’s Julia, who decidedly looks out of place and will act as a sort of “haven” among all the dread and decay you can find in Hanwell, and also the one and only Ambrose Miller, current Head Director of the Institute. People often get in touch with him via the official Hanwell website; he’s a strange and fishy old man alright.

One of Bertrand's four leaked video interviews from Hanwell

Ingmar: What can we expect from the gameplay?

Agustín: The Interactive Teaser released in August was a good example of the direction we want to take, and the final game will expand on those ideas. We want a minimalistic presentation with a clean interface that doesn’t get in the way, so Asylum will be the sort of game that instantly puts you in the “action” without much ceremony. The idea is that players never have to think about the interface and simply let themselves go in the adventure, concentrating on the experience and not so much on the gamey aspects.

This brings me to the puzzles: yes, we do have some traditional puzzling in Asylum, but during the design I often found myself downplaying their role or even discarding entire puzzles to favor the experience. This doesn’t make the game necessarily easier: you still have to pay a great deal of attention to your surroundings, look for clues, plan your next move, engage characters when necessary, etc. So the gameplay is mostly about researching and piecing clues together, and not jumping from puzzle to puzzle; it’s more organic and it should always feel like you’re doing something worthwhile and not wasting time on some isolated brain teaser. Basically, my philosophy was that if some puzzle didn’t provide clear plot advancing, then it had to go.

There are only a couple of exceptions of puzzles that aren’t quite out of place but still not strictly necessary to the plot, and I’m going to tell you about one of them, incidentally taking place early in the game: a very dangerous madman is loose and wreaking havoc in the cafeteria which serves as a nexus to the second half of the first floor. Without revealing any twists, your options are to wait for someone to take care of him (which can take hours and you don’t have that much time) or you can tackle the problem yourself. So you realize how you might calm down the madman by pure observation and deduction, and no inventory puzzling whatsoever. How? Well, you’ll have to play the game to find out…

Ingmar: One of the things that people loved about Scratches was the intense atmosphere that slowly built up until you reached the climax. How would you describe the mood of Asylum, and in what way will it continue the classic Lovecraftian approach of gradually increasing tension?

Agustín: I would say they’re both similar in their design, although Asylum decidedly improves on the defects of Scratches, such as the slow beginning. The script is more dynamic, mysteries are immediately introduced, you get to speak with characters more often than in Scratches, and overall it flows faster. Even so, it’s still a moody and slow game in general terms of the industry.

I recently used an analogy to describe my approach to the design: most horror games like, say, Dead Space, build upon a repetitive game mechanic. It’s basically a suspenseful moment followed by enemies ambushing you which results in a tense battle, then suspense again, another battle ensuing, and so on. If you could distill their design, it probably would look like a sine wave: suspense, ambush, suspense, ambush, etc. And then they plaster a story on top of that. Don’t get me wrong, I loved Dead Space, but flat designs like that leave you with an empty feeling when it’s all over. It’s just a time killer because nothing remarkable occurs in the end.

Now, Asylum is designed in the same way as Scratches: build-up, build-up, a tense moment, more build-up, another tense moment down the road, even more build-up, and then bang, a shocking climax that feels like a sledgehammer busting your head. I know that I ask a lot of you: patience, observation, appreciating the mood, but I think the payoff is worth it. If you compare this design to a horror game like Dead Space, you would see it’s like a tangent always going up. Not much happens in the same way that not much actually happened inside Blackwood Manor, but for some reason the more you play the more anxious and miserable you feel, and it always gets worse as the hours go by.

Ingmar: Another highlight of Scratches was the soundtrack by Cellar of Rats. This time the soundtrack will be done by the German studio Knights of Soundtrack. What can you tell us about the music in Asylum?

|

Daniel Pharos and Agustin |

Agustín: By the time Daniel Pharos first wrote us, Cellar of Rats was already on board for Scratches, but Daniel certainly would’ve been the next immediate choice for the project. As it turned out, Cellar of Rats was the ideal composer for Scratches and I’m positive that Vlad K.’s unique work will be remembered for years to come (especially since he’s left the music industry, so it’s definitely unique).

Just as Cellar of Rats was ideal for Scratches, Daniel Pharos and his team are the perfect fit for Asylum. I was looking from the very beginning for music conveying a darker and more foreboding mood than in Scratches, more in tune with the jarring sights inside the Hanwell Institute. Daniel and co. immediately understood this vision and I’m convinced that they’re on their way to producing another memorable piece of work. Whereas the soundtrack in Scratches had shades of melancholy and hinted of dark secrets, Asylum will be more punishing, evoking a surreal ambiance and arcane, forbidden mysteries.

Ingmar: What about linearity vs non-linearity in Asylum?

Agustín: It’s highly non-linear, yet not as unforgiving as Scratches (which often left you to your own devices with barely any hints). So you can explore the Hanwell Institute any way you want, but larger areas will be gradually introduced. Plus, the next objective you should tackle will be more apparent. For example, from the very first moment you arrive you have access to half the first floor (which is still, like, a lot). However, the protagonist will subtly hint to the player that the next logical step to take would be researching the administrative area, in places like the meeting room, offices, archives, etc. So you have a considerable degree of freedom and can choose to perform tasks in any order you want, but an appropriate course of action is always set for you.

This is an acceptable tradeoff and a definite improvement over the “we-shouldn’t-intercede” policy of Scratches. Over time I realized that people don’t want too much freedom, and in any case it’s better for the narrative. I always find that adventure game design is a delicate balance between freedom players think they have and strings being pulled by the designer. A good analogy would be the so-called Dungeon Masters in a tabletop RPG: they control everything except the decisions of players, which doesn’t mean they can’t tweak the rules to fit their needs and influence those decisions. At least that’s my preferred approach to design: if a game is too linear I feel like I’m being taken for a ride, that the world around me is fake. At the same time, the game shouldn’t be so non-linear that it risks losing my interest.

Never-before-seen screenshot of Hanwell's courtyard

Ingmar: How does the control system of the game differ from Scratches?

Agustín: It’s fairly similar in terms of moving around and controlling your character in Asylum, but the interface has been simplified a great deal. This takes me back to a previous comment about the interface: it’s minimalistic and stays out of the way as much as possible. The basic idea is that you have a notepad on you. Things requiring your attention are listed here, although it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re “tasks” in the literal sense of the word. For example, the first time you meet Lenny, the annotation “Lenny” is added. This basically means that there’s a lot you can learn about him, and once you’ve learned enough the item is marked as completed. Sometimes you do have straightforward tasks you must tackle, such as “Madman loose in cafeteria”. In this case, it means you have to perform some action related to that.

That little notepad you carry around is equally a journal, inventory and dialogue system that helps you to say focused. Clicking on any annotation will make the protagonist say a few words about it, including its current status and what else needs to be done if it’s a complex task. When you’re talking to a character, you can ask about any pending annotation in your journal. Sometimes an annotation can be an item that you’re carrying, in which case clicking on it would mean attempting to use it or show to a character.

As you can see, it’s a very organic system that concentrates everything you need to know about the status of the game at a glance in one single interface element. At first I was worried that it wouldn’t work well, but players seemed to have got the gist of it pretty quickly in the Interactive Teaser, and I’m convinced they’ll grow more accustomed to it as they play the final game. This is quite different than the interface in Scratches, where the inventory system required several clicks to use an item and was rather cumbersome. Still, fans of that game will feel right at home with the interface in Asylum: it’s different in many ways, but remarkably familiar in others.

Another exclusive screenshot of Asylum's morgue

Ingmar: You developed a completely new engine for Asylum (Dagon). Talk about the possibilities this new engine offers and your plans for the technology.

Agustín: Well, there goes one of the things I swore I’d never do again but oops, I did it again. Yes, Asylum is being built with a brand new engine coded from scratch. This is something I seriously considered during the early stages of development: the apparent choices were to either grab the old SCream engine from Nucleosys and improve it, or stick with an existing solution like the young (at that time) Unity, the even younger Pipmak or… I’m not sure we had any more appropriate choices at our disposal. Of one thing I was totally convinced: I wanted to have a very portable engine. The iPhone was already a popular beast and rumors of the Apple tablet were running wild, so I could definitely see Asylum running on one of those devices in the future, and of course I didn’t want to neglect the Mac and Linux platforms.

I won’t go through every bit of reasoning that led to this crazy decision; suffice to say, Dagon (formerly known as Kinesis) was born out of need. I’d have loved to continue work on SCream, but that engine was dated and quite messy to tell the truth. Dagon went through three complete rewrites until reaching its current form (yes, I can get a little obsessive) but the goal was reached: the engine allows the programmer to completely ignore the underlying system with a friendly and simple scripting language.

It’s still rough around the edges, but several non-programmers have been able to code stuff with it. Even better: the portability does work. For example, the Interactive Teaser shares the exact same code and resources among Windows, Mac and Linux. It will mostly be the same in the case of the iPad and other devices, except that the format of the resources has to change (because more compression is needed in those distributions). One of the Dagon developers recently sent me a demo of her game that was fully programmed on Windows and I could load it without a hitch with the Mac interpreter.

Gameplay video from Asylum shows off the Dagon engine in action

Anyway, I don’t take the portability aspect lightly, especially in the case of adventures. We need to reach a wider audience and I fear the Windows crowd won’t be enough any longer in the near future. Many existing engines are neglecting other systems and I believe this is a huge mistake. You wouldn’t believe the amount of Linux users that received the Interactive Teaser with open arms and are now anxiously looking forward to playing the final game.

As for other aspects, the engine was built exclusively with adventure games in mind, although it’s flexible enough to support other types of games (for example, you could easily do a Hidden Object game right now). Because of this it’s speedy and doesn’t require a very powerful computer. For now it’s focused on first-person adventures (both panoramas and slideshows) but eventually we’ll add support for third-person. The output of graphics is very “elastic” and automatically supports any type of resolution, including true HD. For example, you can try resizing the Asylum teaser any way you want while in windowed mode: “it just works”.

We briefly considered commercializing Dagon but decided it was best to give it away for free. I’m not sure how much money we could’ve made with it; probably not much, and in any case it’s always good to support the adventure community and in doing so reinforce the presence of Senscape in the market. As long as the community does well, we’re all going to be fine. So the engine is already freely available with the Interactive Teaser, which also includes its source code as an example, and eventually will go open source. I’m probably nuts to give away work that’s worth around two years of man hours but, you know… yeah, I’m nuts.

Ingmar: Everyone who’s read Lovecraft knows that your games have a strong Lovecraftian vibe to them. Talk about how he has been an influence on your own work.

Agustín: What can I say, I’m old fashioned. I love the horror stories of yesteryear, highly descriptive with dense proses, and how they were mostly constructed around this huge, terrifying twist; that final revelation that gave a whole new horrific meaning to an already frightening story. Many of Lovecraft’s tales work this way, which is precisely how I described my approach to horror game design: it’s a constant build-up until this shocking revelation, usually the final piece of a puzzle that you needed to form a sinister picture. The Case of Charles Dexter Ward had such a reveal, explaining something that you read about yet previously couldn’t understand in a deeply disturbing way.

This is the feeling I get when I read stories by Lovecraft and his contemporaries: it’s all basically a big setup. Problem is, this effect can be hard to achieve in games that require input from a player; you need to have interaction, and therefore actual stuff going on in the story to maintain the interest and drive the plot. Let’s take another example such as At the Mountains of Madness: this is undoubtedly one of the best horror novels ever written, and yet the story is quite uneventful. It’s pure mood. Sure, the protagonists find an ancient city, they do some exciting research, but in the end all of this is just a huge preparation for a fateful sequence when they meet the final horror. And that’s when the story ends. If Mountains of Madness was an adventure, its walkthrough would only be a few lines long.

I only understood years later just how much Lovecraft had influenced Scratches. It was always about the twist and the whole story was constructed layer by layer around this final revelation. For example, the African angle was a later addition to provide more depth to the whole thing; of course, I had to make it feel like a game and fortunately mysteries translate very well to adventures. Still, the concept remained the same: build-up until that final horror and then everything ends abruptly, just like a Lovecraft story.

Many hated this type of ending because they were expecting closure, such as what happens after the shock (which gave birth to the idea of The Last Visit, but that’s another story). I was always careful to make sure that all the clues to put together the mystery were present in the game, if not at first sight, then easily understandable upon subsequent replays. However, the ending had to be instant and shocking, like that final revelation in Dexter Ward.

Lovecraft was such a huge part of my childhood, easily being my favorite writer, that I don’t think I’ll ever be able to write a horror story that doesn’t adhere to this concept. I’ll admit that the twist sometimes doesn’t work as expected (and some endings by Lovecraft certainly felt forced), but when it does, it’s pure magic.

First Asylum teaser

Ingmar: There have been tons of games related to Lovecraft in one way or another. How do you feel about the Lovecraft-inspired games you’ve played and how do you think they’ve managed to capture the spirit of Lovecraft? For example, many people complained that Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth ruined the immersion by showing all the creatures you usually have to imagine yourself.

Agustín: Yes, that happens all the time. I’m not sure if the misinterpretation of Lovecraft’s work is intentional or a failed attempt to capitalize on it, but the result is terrible: nowadays most people think that Lovecraft is synonymous with bizarre monsters that defy description and that’s it. This is such a shame, because there’s so much more to Lovecraft’s stories than the monsters. In fact, I would go so far as saying they were always secondary plot devices. Lovecraft’s obsession was with the unknown that we can’t assimilate, forbidden knowledge with the power to drive us insane, and the minor role of humanity among a battle of ancient powers escaping our understanding. In short: we know nothing, and if we did we couldn’t take it. Very little of those concepts have made it to movie or game adaptations.

There’s another cornerstone of his work that nobody has yet managed to replicate and that’s the “cosmic horror”. Lovecraft was the first person to tell us “space is not beautiful, it’s scary”. This earth-shattering concept that has influenced hundreds and hundreds of writers (many consider this the basis for modern Science Fiction) is sorely missing from most adaptations carrying the Lovecraft name. There’s one line in The Colour Out of Space, one single line that I believe exemplifies his work: “I vaguely wished some clouds would gather, for an odd timidity about the deep skyey voids above had crept into my soul.” Wishing for clouds because the blue skies, commonly accepted as a “good thing”, are intimidating. That mind-blowing concept is what Lovecraft was all about.

So fear of the unknown is the key. Fear of what lies beyond, of what could happen. The irrational fear that some kind of ancient creature soaring the skies might notice you if clouds aren’t there to protect you. If done well, that is infinitely more effective than deformed monsters occasionally jumping at you. Remember: pretty much every Lovecraft tale can be dissected as a protagonist that digs too much into arcane secrets that weren’t meant for humans. They all eventually lead the protagonist towards an unspeakable horror and one final, shocking revelation. Sometimes he doesn’t even get to meet that horror! How many games work like that? How many action games do you think could sustain that type of plot? Luckily we’re discussing adventures here.

Ingmar: Which other adventure game developers do you admire, and for what reasons?

Agustín: At this point I admire anyone that is still working with adventures. Seriously, there’s so much prejudice against the genre, making it so difficult to attract an audience and find ways to distribute your work, that only the most passionate people will even care to try. Fortunately, there are many of us out there. But more specifically, I’ve always admired all the Sierra developers. It is my favorite software company ever, so it makes sense. They pioneered the graphical adventure and you can clearly witness by playing their entire catalogue how they were evolving and experimenting with exciting possibilities with each new title. The relaxed working environment in the early days of Sierra (as described by many ex-developers) truly showed in their games, conferring to them a sense of charming naivety. The Williams, Scott Murphy and Mark Crowe, Al Lowe, Josh Mandel, Lori and Corey Cole, the Murrys, Jane Jensen… They’re my heroes.

I do have to mention Legend Entertainment and everyone involved with that company as well. I’m a die-hard fan of their entire output (I can’t even say that of Sierra!) and the whole philosophy behind their games. Nearly every title they produced excelled in narrative and challenging, organic puzzles, and their engine remains the best for Interactive Fiction. Particularly, Bob Bates has proven himself to be among the most versatile game designers that ever worked in this industry, as he produced critically acclaimed titles in mystery, adventure, sci-fi, comedy and horror genres; how’s THAT for diversity?

Second Asylum trailer

Ingmar: You're known as someone who puts a heavy emphasis on strong storytelling. Which adventure games have impressed you in terms of narrative throughout the years?

Agustín: Precisely, many Legend games. I think they were the epitome of the term “Interactive Fiction”. Perhaps not the most significant or influential examples but quite possibly the most realized ones. Games like Eric the Unready and Gateway 2 felt like an exquisitely written novel unfolding in front of your eyes. Puzzles and story were one indivisible force, and the designers often achieved perfect flow: Eric has some of the most satisfying puzzles I’ve experienced in adventures, and is perhaps the only IF title that really made me laugh out loud; similarly, it’s amazing how much action and excitement they managed to convey in Gateway 2… the first moments are truly riveting, and it’s all mostly text!

Moving to graphical adventures, and staying with Legend, Death Gate and Mission Critical would be the most impressive ones. Again, Death Gate as a magical adventure with near-perfect puzzles and Mission Critical being hands down one of the best sci-fi games ever produced (and a strong influence in the next game from Senscape!). Of course there’s Sierra, with the refreshingly mature Gabriel Knight series and King’s Quest 3; the latter is a curious choice, granted, but I remember that story-wise it was a far cry from the first title in the series: the setup, you being mysteriously confined in an old house atop a mountain by an evil sorcerer without knowing your identity, was pure gold. That was probably the first great achievement of Sierra in terms of storytelling and the first time I felt my brain working at full speed while playing a game: half of it was focusing on the present events and solving puzzles, while the other half was trying to decipher the story and anticipating the twists.

Then, I would have to mention Full Throttle, which literally absorbed an entire afternoon of my life with its fantastic plot. It’s a short game and very lightweight on puzzles, but amazingly paced. I kind of love road movies, so there’s a reason why I liked it so much. It has one of the best endings in adventures too. And speaking of endings, I couldn’t forget about The Last Express: another game that transported me to another time and place with a majestic execution. It allowed me to experience this charming mystery in a really unique way that hasn’t been reproduced ever since.

Ingmar: What is your view on the state of storytelling in adventure games these days – especially when it comes to games for a mature audience?

Agustín: I feel that current adventures remain at a crossroads of sorts. We’re still leaving behind a bad period for the genre when many (even fans) didn’t hesitate to claim it was dead. That was never the case, of course, and nowadays it should be more than evident, but we seem to be heading towards the exact opposite direction: instead of pushing the genre forward, we’re spending too much effort rehashing old ideas. This is not entirely bad in itself, but the industry has changed a lot since the heyday of adventures. This “naivety” I mentioned when I was talking about Sierra was wonderful back then, but today it only appeals to a reduced audience. The rest has moved on and demands more thought-provoking, lifelike experiences. I fear this adventure game “revival” in the end will hurt more than benefit us because the problem isn’t bringing back adventures but adapting them to the standards of these days.

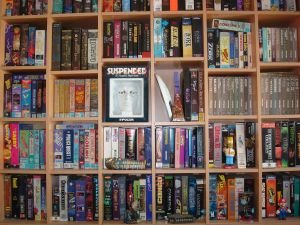

|

Agustin's impressive collection of classic adventures |

Still, I’m speaking in very general terms. We don’t need every adventure released today to be mature (heck, we certainly need more games like Machinarium or The Book of Unwritten Tales in the industry) but I do feel that we need more dramatic, adult experiences; otherwise we’re giving the wrong impression. The mainstream audience looks at us and thinks we’re a bunch of nostalgic losers wasting time with a dead genre. Part of me doesn’t give a damn what a kid obsessed with Call of Duty thinks about adventures, but another part understands it’s a serious problem. What I observe is that the adventure audience remains stalled; there are many of us, yes, but we’re failing to attract newcomers. This leaves the genre in a precarious condition, each passing day making it more difficult to market and sell adventures.

Ingmar: We do certainly seem to be in the midst of an unprecedented revival, with one exciting thing happening after the other (Tim Schafer, two new games by Jane Jensen, the return of Tex Murphy, Broken Sword 5, Tornquist’s comeback, etc.). What do you think of all the recent developments?

Agustín: As I was saying, I love this revival, even if in the end I don’t believe the current wave of upcoming titles will improve the generalized perception of adventures. What I do hope is that they’re successful enough to warrant both returning and new developers alike to be able to produce less compromised titles. By “compromised” I mean games that are tied to the past with backers or fans expecting them to live up to the classics. We shouldn’t have that sort of expectation and should be more open minded about the offerings of these developers.

For example, I know many want SpaceVenture to be the next Space Quest, or Moebius the true successor to Gabriel Knight, when in reality we should be telling them “surprise us!”. In the meantime, fresh titles like Cognition are having a tough time getting noticed. I’m not saying the new titles from the returning designers aren’t original or worthwhile; not at all, but they’re too dependent on the past to signal a true renewal of the genre. And in a way I’m guilty of that myself with Asylum, which irremediably will be judged under the shadow of Scratches. I just hope this is a transitional period and very successful for everybody involved, so that next time we all have the time and resources to do something truly new and uncompromised.

My biggest concern is that the health of the genre likely will be determined by the success of this new batch of “big” titles; if not by us, then by the mainstream press. And there are way too many hopes and expectations attached to them, unnecessarily I must add. Let’s not forget about the Wadjet Eyes, Daedalics, KING Arts, Pendulos and many others that deserve just as much attention. They have been keeping the genre alive and kicking all this time, which was never dead to begin with and never will be. The great breakthrough we’re all expecting (the beginning of a new golden age, some may fantasize) isn’t going to happen now. But we’re slowly getting there, that’s for sure.

Ingmar: Even though you’ve become a developer you have always remained a fan. From the perspective of a fan, which of the upcoming adventure games do you look forward to?

|

Agustin (and Sackboy) pose at this year's gamescom |

Agustín: I’m dying to play all of the recent Kickstarted adventures. Of course this is contradictory with my feelings about the present status of the genre, but I’m speaking as a die-hard fan of adventures now. In particular, I’d have to single out SpaceVenture, being the rabid Space Quest fan that I am. In a similar vein, Jack Houston and the Necronauts looks deliciously charming. Actually, most of my favorite upcoming titles are sci-fi adventures: ASA: A Space Adventure, Cradle, ETHER, Prominence… Up until recently there were close to no new sci-fi adventures and now we have so many of them. You know what they say: when it rains, it pours.

Sure enough, I’m always looking forward to the next titles from Jonathan Boakes and Matt Clark. Those guys know their stuff.

OH! And the next episode from The Journey Down. That one got me completely hooked. I wanna Bwana!

Ingmar: You said that Asylum will be your last horror game for a while and that your next adventure will be science fiction. Anything you can tell us about that game?

Agustín: Yes, I’d like to hang the horrific gloves for a while after we’re done with Asylum. The next game is a fairly well developed idea and it could have been our first choice for Senscape instead of Asylum. Its setting is a distant future when resources on Earth have been exhausted; relocating the entire population is deemed impractical, and in order to survive, humankind must travel to faraway galaxies to scavenge anything they can.

This is achieved by means of a revolutionary system that allows nearly instant transportation of materials across vast distances in space with one caveat: living beings never survive the process. Thus, only a few humans can engage in excruciating long travels by more “typical” faster-than-light speed to establish small colonies in the recondite corners of the universe. In one of those galaxies they happen to pick up the trace of an ancient civilization that has long since vanished from their home planet; at first they seem nothing like us, yet further investigation starts to reveal startling human traits…

The game will aim to propose deep questions about humankind, our place in the cosmos and our “goals” (if any!).

Ingmar: What else can you tell us about the future plans of Senscape?

|

Agustin and his wife Alina soak in a very familiar sight to adventure gamers |

Agustín: I just wish that Asylum is successful enough to allow us to continue working on adventures. I have lots of faith in the genre but it’s true that developing and marketing adventures is becoming tougher each passing day. The future isn’t so grim though: the community remains strong and very dedicated, and with tools such as Kickstarter at our disposal, and social networks to keep in touch with the fans, I’m sure that we’re all going to keep striving.

Speaking of communities, I’m hoping that what we’re building with the Dagon engine grows larger and developers can benefit from it. I do have ambitious plans that eventually would turn Dagon into something bigger than an engine, not just to play adventures but a platform that would bring people sharing the same interests together… but one step at a time. For now, we’re already quite busy with Asylum.

Ingmar: Thanks a lot for investing so much time in this interview, Agustin. Any last words until we do it again?

Agustín: Thank YOU! And I promise the next interview won’t be three months in the making (or was it four? I’ve lost track of time!). It will be shorter too. What’s the current tally now? Let me check… SWEET SHOGGOTH ROLLING DOWN THE MOUNTAINS! 10,000 words! I have to wrap this up at once…

Anyway, I’d also like to thank all the readers for their endless patience and support. Yes, Asylum is taking a long time, but only because we want to create something that will leave an ever-lasting impression on you; an engrossing experience unlike any other. Having the opportunity to do this, working in the adventure genre and being in touch with thousands of fans every month still seems unreal to me. It’s an immense pleasure being able to contribute in any way to the legacy of what is unquestionably the best game genre ever, and my ultimate goal is to provide people with that same sense of wonder that I felt when I first launched King’s Quest over two decades ago.