Casual adventuring: Sherlock Holmes and the Women’s Murder Club

Categorizing games in these days of ever-blurring gameplay lines is a bit like delving deeper into the Amazon rain forest and finding new orders, new genera, even whole new species everywhere you look. Sadly, I've not been granted the authority to name any new sub-genres of games, but I do have the responsibility to play those that look like adventures, sound like adventures, and even claim to be adventures. Two such games released recently are The Lost Cases of Sherlock Holmes and Women's Murder Club: Death in Scarlet, and while both prove to be a little too "casual" to be deemed full-fledged adventures after all, they're certainly in the same family, sharing more than a few similarities that should appeal to both adventure gamers and casual players alike.

This resemblance shouldn't be considered all that surprising, given the subject matter and pedigree behind the two titles. Fictional crime mysteries are a staple of the genre, Sherlock Holmes a frequent guest, and Lost Cases is from Legacy Interactive, better known for their Law & Order adventure games before turning their attention to the casual game market. Death in Scarlet, meanwhile, is the first game based on James Patterson's popular Women's Murder Club novels. It also happens to be designed by none other than Jane Jensen, creator of the acclaimed Gabriel Knight thrillers who went on to became the co-founder of Oberon Media and a leading proponent of casual games.

Of course, referring to "casual games" isn't overly descriptive in its own right, as it's simply an umbrella term for any pick-up-and-go experience that can range from twitch-based puzzlers to life sims, from crosswords to solitaire. Deeper into the genre jungle we must go, then, to the "hidden object" phylum. Or seek-and-find games, if you will. Kind of a Where's Waldo? mother lode. For the uninitiated, the central task of such games is simply to find a series of random items concealed in densely designed backgrounds, generally including a few standalone puzzles to vary the gameplay and a loose storyline tying the experience together. They're simple, single-mindedly goal-oriented, and surprisingly addictive. They can also be remarkably different from one another, as these two prominent recent additions will attest, so a closer look is in order.

The Lost Cases of Sherlock Holmes

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's famous detective has starred in many adventures over the years, and The Lost Cases of Sherlock Holmes is marketed as a "lavish mystery adventure game", but the new game shouldn't be confused with the likes of Frogwares' ongoing series or the classic, similarly-named Lost Files of Sherlock Holmes titles. It does happen to be the first game officially licensed by Doyle's Estate, though this distinction doesn't seem to make much practical difference. The use of Holmes as a central protagonist, however, does offer an appealing narrative lure and more importantly, a different spin on the familiar hidden object gameplay formula.

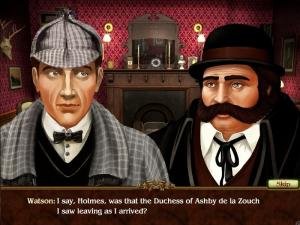

The game is split into 16 distinct chapters, with each revolving around a new crime to be solved, from murder to blackmail to cat burglary, and plenty in between. New cases are introduced through a non-interactive dialogue establishing the details of the crime, often treating players to visits from old favourites like Inspector Lestrade and Sherlock's brother Mycroft, and of course Dr. Watson as the trusty sidekick. Surprisingly for a casual game, these dialogues are fully voiced, and the solid vocal performances all do full justice to the famous characters they portray. The hand drawn portraits during these sections are designed nicely, but a little too simplistic and cartoony in comparison with the rest of the game.

The game is split into 16 distinct chapters, with each revolving around a new crime to be solved, from murder to blackmail to cat burglary, and plenty in between. New cases are introduced through a non-interactive dialogue establishing the details of the crime, often treating players to visits from old favourites like Inspector Lestrade and Sherlock's brother Mycroft, and of course Dr. Watson as the trusty sidekick. Surprisingly for a casual game, these dialogues are fully voiced, and the solid vocal performances all do full justice to the famous characters they portray. The hand drawn portraits during these sections are designed nicely, but a little too simplistic and cartoony in comparison with the rest of the game.

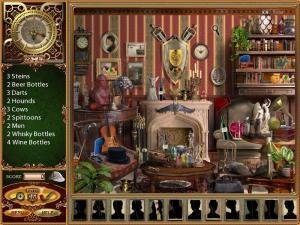

The graphics throughout the hidden object portions of the game are appropriately detailed, covering 40 different historically accurate locations from Victorian era London, with stops at the Diogenes Club and 221b Baker Street for good measure. A few higher resolution options would have been preferable, but what's provided is certainly acceptable. Many of the items to find are small and hard to spot with the naked eye, but here Lost Cases makes good use of one of Sherlock's familiar detective instruments. With a quick button click, you can activate the magnifying glass, which makes a big difference in picking out details you'd otherwise miss. While both necessary and admirable in concept, however, I'll admit to not being too fond of using it. The area covered isn't particularly large and yet it's highly magnified, so the exercise feels less like scanning specific items up close and more like sweeping the screen for indiscernible lines and patterns.

Along with the magnifying glass, the most distinctive difference from most hidden object games is what you're looking for. Usually you're tasked with finding a list of objects seemingly pulled from a hat, which would make no sense at all in a serious role like Sherlock Holmes. There are still a handful of such searches (and they're every bit as out of place as they sound, despite a rather weak attempt to justify them), but for the most part you'll be examining two images looking for differences. The screen is split in half horizontally, with the top and bottom representing before-and-after contrasting scenes. What you're trying to find, then, are objects that exist in one and not the other, or are slightly altered in some way. A similar comparative exercise is used for specific items occasionally, like paintings or guns. This is totally in keeping with logical investigative technique, and feels more organic to the process.

On the flip side, the mandatory time limit feels completely contrived. Only once in the game did I come even remotely close to running out of time, but the pressure tactics detracted from the experience, especially as speed was never rationalized by the story ("Quickly, before the killer strikes again!"). Some hidden object games have wisely dispensed with time limits or made them optional, and Lost Cases would have been better served following suit. Still, there are a reasonable number of hints supplied, so most players shouldn't have any difficulty getting through the levels in the time allotted.

There are plenty of other puzzles to solve when not scouring crime scenes, some worked in more seamlessly than others. Experienced adventure gamers will find a laundry list of familiar puzzles, including the likes of sliders, jigsaws, cryptograms, anagrams, and various Simon-like challenges. You can bypass a limited number of these puzzles entirely if you wish, but at the cost of a fairly significant time deduction. Fortunately, since most are quite manageable in difficulty, this shouldn't be much of an issue. Each case is concluded by arranging suspects in a thematic Sudoku sort of puzzle, and then "deducing" the culprit. I use the word loosely, as there's no real deduction involved, just following a pre-determined process-of-elimination memory minigame until Holmes surprises everyone with a convoluted resolution only he could have reached.

In fact, the lack of any sort of actual case analysis is one of the bigger disappointments throughout the game. Suspects, increasing in number from six to twelve as you progress, are simply announced upon discovery of a particular object that somehow incriminates them. This is done through an intrusive text box that brings the game to a screeching halt often enough that you'll start to resent them. There is an option to switch this feature off, but then you end up with a group of suspects automatically compiled with no explanation at all, which detaches you further still from the already slim narrative.

In fact, the lack of any sort of actual case analysis is one of the bigger disappointments throughout the game. Suspects, increasing in number from six to twelve as you progress, are simply announced upon discovery of a particular object that somehow incriminates them. This is done through an intrusive text box that brings the game to a screeching halt often enough that you'll start to resent them. There is an option to switch this feature off, but then you end up with a group of suspects automatically compiled with no explanation at all, which detaches you further still from the already slim narrative.

Of course, by the time you've finished the game in five or six hours (add a couple if you're more Watson than Holmes), you'll have long since adjusted any false expectations going in. This is not a traditional adventure, after all, so lay to rest any hopes of deep plot, freedom of exploration, character interaction, or even consistent puzzle integration. As a casual title, however, The Lost Cases of Sherlock Holmes is a solid hidden object game with some clever gameplay twists and a nice use of the license, and the biggest challenge may just be resisting the next case… and the next… and the next…

Women's Murder Club: Death in Scarlet

While many adventure fans are (im)patiently awaiting Jane Jensen's Gray Matter, the acclaimed designer managed to squeeze in Women's Murder Club: Death in Scarlet in the meantime. Having previously tried her hand at other casual adventures like the Minesweeper-based BeTrapped!, Jensen served as both writer/designer and Creative Director of Death in Scarlet, and the result is easily one of the most polished, engaging hidden object games available today. It is also, as advertised by the designer herself in a recent interview, "the most adventure-game like casual game Oberon has done."

The most obvious area that Death in Scarlet stands out is its storytelling. As predictable as that may sound for a game based on a book series, all too often story is given short shrift in casual titles. Here it's given at least equal footing with gameplay, and the integration of the two is head-and-shoulders above most (if not all) of its contemporaries. Of course, the fear of such an approach is that it could jeopardize the "casual" nature for those who only play sporadically and don't want an involved plot that's easy to forget. Fortunately, while the game does follow a single escalating murder mystery, it's broken up nicely into manageable chapters, and there's lots of handy reference material to review if returning players need a recap.

I wasn't familiar at all with the Women's Murder Club franchise prior to playing, but like the novels, the game follows the exploits of San Francisco police detective Lindsay Boxer, forensic examiner Claire Washburn, newspaper reporter Cindy Thomas, and lawyer Jill Bernhardt. Jill makes only an occasional supporting appearance, but the other three are all playable characters, so fans of the books or the short-lived television show should feel right at home.

The story, created specifically for the game, centers around a series of murders whose clues demonstrate an alarming adherence to ultra-conservative Chinese values. The cultural foundation is important, as it's both literally and figuratively foreign to the young Americans investigating the case. The majority of the game is played as Lindsay as she tracks down various leads, but players will also do lab tests and return to crime scenes as Claire, whose expertise requires her to look for different things, while Cindy helps with research and a bit of additional legwork. Even though none of the characters speak, and you can't interact with them directly, the constant changing of playable characters, each with their defined roles, gives the game a refreshing blend of perspectives.

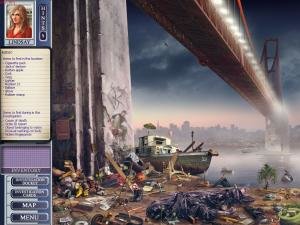

Virtually every scene has the requisite list of hidden objects to discover, of course. Once again, this represents the one glaring contradiction to the narrative. To the game's credit, you are required to look for evidence relevant to your case, but these are in addition to the standard random list of objects. So on the same screen, you'll feel like an investigator looking for poison on a corpse's lips, while moments later looking for a crab, the letter "Q", or an inconsequential ruler hidden in the rafters. But hey, it is a hidden object game, so be forewarned.

The nicely designed environments, from a ship's deck to the "Deadlines" café to a variety of Asian-accented locations, are not overly cluttered with extraneous junk to sift through. The objects themselves tend to be a little too small, however, and on more than one occasion I wished I had Sherlock's magnifying glass handy. There are a handful of hints available (and by "hint" in these games, I mean "blatantly showing you where a missing item is") if you're stuck, or you can persevere on your own, because there is no time limit at all in Death in Scarlet, so you're free to take as long as you want. There's also no penalty for clicking on the wrong item if you resort to random guesswork.

The nicely designed environments, from a ship's deck to the "Deadlines" café to a variety of Asian-accented locations, are not overly cluttered with extraneous junk to sift through. The objects themselves tend to be a little too small, however, and on more than one occasion I wished I had Sherlock's magnifying glass handy. There are a handful of hints available (and by "hint" in these games, I mean "blatantly showing you where a missing item is") if you're stuck, or you can persevere on your own, because there is no time limit at all in Death in Scarlet, so you're free to take as long as you want. There's also no penalty for clicking on the wrong item if you resort to random guesswork.

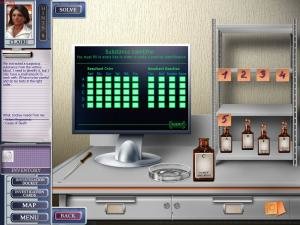

Some of the objects you find will be stashed in a small inventory that gets used in that area, while at other times you'll enter a scene with a few basic tools you'll need. None of these inventory puzzles are at all difficult, but it's a bit more engaging than having everything done for you. That isn't always the case, though. At times Death in Scarlet seems to go out of its way to make the game easier. Many of the standalone puzzles with movable parts will lock correct pieces in place, which all but prevents you from failing, while others won't allow failure, period, like a tangled rope puzzle where you can do nothing at all except click on the next rope to pull free. But the most blatant of these silver platters comes during a repeated lab puzzle that is already easy to begin with, but could have been a diverting exercise if left alone. But it wasn't. Claire must test various liquids for colour and reaction that you'll need to select from a pre-defined list. Now, I'm pretty sure I could identify yellow and smoking from purple and boiling using my own keen senses and penetrating intellect, but just in case I couldn't, the game helps out by plastering a large-print "Purple boil" right over the experiment. Believe me, I'm all for user-friendly features and increased accessibility, but there's got to be a line drawn somewhere, and Death in Scarlet overshoots it a few times too often. At the very least, such help should be made optional, especially since it's possible to skip a puzzle altogether if you're stumped.

None of the other puzzles will pose much difficulty for even partially-experienced adventure gamers, but there's a nice mix to vary the gameplay, even if some seem ill-suited to a police investigation. Several are character-specific, like a bottle sequencing puzzle (C before E but not between A and D, etc.) that Claire must solve before getting to each of her self-solving experiments. Cindy, meanwhile, has to keep organizing her office by solving themed Sudokus or earning information by winning a hangman-styled minigame. Other puzzles scattered throughout the game involve keying basic search info into a computer, jigsaws, clue and pattern matching exercises, and a fun overhead maze-like puzzle to strategically corner a suspect, to name a few.

With the challenge kept to a minimum, the game moves along at a snappy pace in a linear fashion. Characters communicate with each other after completing their assignments, and stylish comic-like cutscenes progress the plot between chapters, giving the game an admirable depth for its limitations. I finished the game in well under five hours, but I felt like I'd come a long way in that short time. And had a darn good time doing it. I'd have gladly spent more time with the Women's Murder Club, but I fully expect to see Lindsay and the gang back in future adventures. Err… did I say "adventure"? I suppose I did, and not entirely by Freudian slip, though I meant it more in the literal sense than a genre interpretation.

Casual Conclusion

For fans of casual games, The Lost Cases of Sherlock Holmes and Women's Murder Club: Death in Scarlet should each provide several absorbing hours of entertainment, though probably not much more in terms of replayability, as the mysteries aren't randomized in either case. If choosing between them, both have specific strengths that serve the game in different ways. Where Lost Cases offers a different slant on hidden object sleuthing, Death in Scarlet provides a far more cohesive experience between story and gameplay. Each game is budget priced and available for download already, Lost Cases from Legacy Interactive and Death in Scarlet from Oberon Media, among other popular download portals. And for those who like their games on disc, Sherlock's game has already been released to retailers, while the boxed Women's Murder Club mystery will be available this August, reportedly including a novella and 50-odd teaser pages from James Patterson’s next novel.

If you're an adventure game diehard and wondering if casual games could possibly be worth your while, that's more difficult to answer, though either of these games could be considered deserving places to test the waters if you feel so inclined. A case could probably be made for simply labeling both games as (lite) adventures by the broadest of definitions, and the goal here isn't to exclude them as such, just to raise awareness of the both the similarities and differences that can be expected. For many, seek-and-find games could just prove to be the core experience they love in adventures with all the excess trimmed away, while for others they may be little more than diversionary filler with no real substance. That's for you to decide, and both games have playable demos to help you along. Just don't be quick to discount them sight unseen, as their appeal may just be the most important object currently hidden from view.