Adventures in Storytelling: The Maker’s Eden, 80 Days page 2

While story, exploration, and puzzles are (and will always be) the central pillars of adventure games, more and more narrative-driven games – if they can even be called "games" at all – are opting to forsake traditional adventuring in favour of more straightforward, streamlined interactive fiction. Led by the likes of Telltale Games, this growing sub-genre focuses on storytelling at the expense of all else, with varying degrees of player agency affecting the plot through the choices they make. Two recent examples are The Maker's Eden and 80 Days, which demonstrate just how diverse such experiences can be.

The Maker's Eden - Act 1

Pascal Tekaia

Developing a visual novel and calling it a game may be a bit of a gamble. Whether or not a particular title mixes story with enough interactivity for it to actually be considered a “game” is frequently discussed, with supporters making arguments on both sides of the debate. Of course, different titles fall on varying places of the spectrum.

In the case of the debut episode of The Maker’s Eden, the level of interactivity is quite low, resulting in something more like a digital comic book – albeit an interesting one – in which the player’s main role is to “turn the pages” by clicking on the screen and reading the dialog and narration as they’re presented.

The story premise is not exactly unfamiliar, as science fiction fans will recognize the influence of films like Blade Runner reflected in The Maker’s Eden. It is set in a dystopian future in which mankind has created androids, a brand new species designed to perform undesirable labor. Though created as a means to an end in bringing a new level of comfort to humans, androids have gained some level of consciousness. Discriminated against and forced into servile positions as a lower class of being, androids now strive for equality among species, creating a bubbling cauldron of Civil Rights-esque classism and paranoia.

The game centers around 905, an android awakened from his sleep-like stasis in a derelict apartment building. Named after the number of his stasis pod for lack of a proper name, he finds he has no memory of who he is or why he is there. However, he soon finds a hidden message warning him not to trust Didymus Industries (the people who’ve awoken him only moments earlier) even as they attempt to bring him to their headquarters. After a daring escape, 905 finds himself on the run from the authorities (who are deep in Didymus’s pockets, of course) and must gain the trust of an underground android resistance movement to uncover his identity and learn why the evil corporate entity will go to great lengths to get their hands on him.

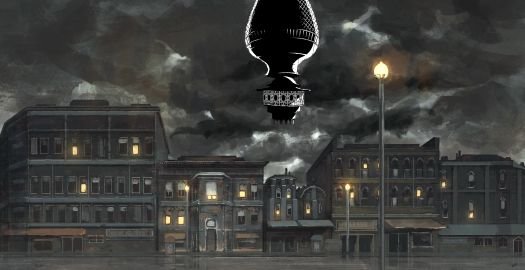

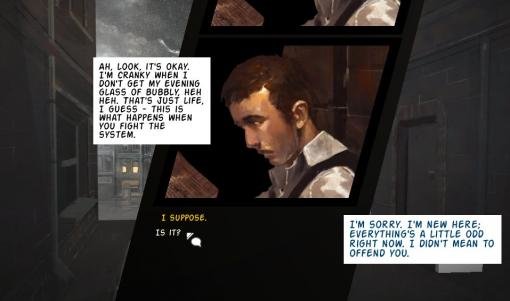

In keeping with the graphic novel theme, the game’s dialog and exposition occur via a mix of traditional descriptive text that appears when clicking on objects in the environment, and close-up panels of other characters when conversing with them. The entire game is shown from a first-person perspective, with individual screens that are 95% static images (with a few environmental or weather effects to liven them up) along with a neat quasi-3D effect that separates the foreground from the background when panning the camera a bit to the left or right. While they don’t quite steal the show, the hand-drawn graphics acceptably serve the atmosphere, showing just enough run-down detail to lend the game a sense of gloomy depression.

Events take place on a rainy night, and you’ll split your time between wet streets and dingy indoor locations, derelict and mottled-looking. Predictably, the color palette on display runs the muted gamut of all shades of browns, grays, and dark blues. This neatly coincides with the nocturnal setting and general squalor of the city, but even in locations that should have been more luxurious, such as the flat of a well-off family or an executive office suite, the surroundings are uniformly haggard and ugly, all displaying the same threadbare decorative style. It doesn’t help much that the graphics are somewhat smudged and lacking focus, as if a low-res photo had been enlarged and used as background art.

Initially, I was pleased by the game’s low-key jazz soundtrack. At least, until I realized that every screen throughout the game simply repeats the same track over and over. Apart from distinct tunes for the menu screen and a brief moment near the game’s end, this makes for a score that’s very light on variety, which would have been a much bigger concern if the game were long enough to draw attention to this shortcoming. As it stands, with a play time of just over an hour, chances are you’ll likely never even notice that the music stays pretty constant throughout. It’s not bad – in fact, the song sounds rather good and very noir-ish – but it’s all you’ll get.

What will doubtless be a much bigger concern for players is the fact that this interactive novel really skimps on the “interactive” part. Often you’ll function merely as a tool to advance through the dialog by clicking and (sometimes) selecting from two or three different responses during conversations. This lends a false sense of “choose your own adventure”, as all dialog choices veer off into different directions for a moment only, and then immediately converge back onto the same path to keep the conversation flowing along. I was unable to find any response choices that actually had an effect on the outcome of a conversation or the game as a whole. The dialog options are really more akin to standard adventure game conversation topics – they lead to some new dialog, but once that’s out of the way, you’re led back to the main conversation.

Inventory puzzles – heck, puzzles in general – don’t fare much better. While 905 does pick up an item or two during the adventure, they can’t be manipulated or even selected at will. Instead, progress operates more on the principle of “you’ll only get past the door if you’ve already picked up the key” – everything happens automatically. You never actually see your inventory or have a choice of how and where to use it; progressing simply requires finding the right order of clicking on objects and interacting with characters. Outside of this, there are really only two other puzzles to solve, one requiring turning dials in a certain pattern, the other to line up tiles to create a path.

I don’t mean to go overboard with the negatives about The Maker’s Eden: Act 1 – fans of visual novels will find several things to like here. It’s a science-noir-styled tale that holds some interest, and a difficulty curve that is accessible to even the most reluctant gamer. Indie developers Screwy Lightbulb are even filling in the gap between this and the next of the three planned installments through short graphic vignettes, accessible from the main menu and releasing via free download at regular intervals. Centering on various individuals 905 meets in the game, these vignettes are intended to flesh out the supporting cast a bit more and simultaneously add some content to the game’s noticeably short runtime.

If you value exploration and puzzles over story in your adventures, be forewarned that The Maker’s Eden (available through Steam) doesn’t pretend to straddle the fence, instead sitting quite comfortably on the “novel” side of “interactive novel”. Despite being light on actual gameplay, however, fans of this developing sub-genre just might find it to be worth a look.

80 Days

Scott Bruner

A number of companies have tried to adapt interactive fiction-style adventuring to the lucrative mobile market – such as Choice of Games’ gamebook stories – but no company has had as much success as Jon Ingold’s UK-based company inkle. A year after releasing a mobile version of Steve Jackson’s first Sorcery! gamebook, inkle’s newest release, 80 Days, continues to evolve their model for interactive fictional narratives, and has scored an equally impressive success.

80 Days – not to be confused with the 2005 Frogwares adventure by the same name – is a very liberal adaptation of the Jules Verne’s classic Around the World in Eighty Days. Although the game is billed as the next technical evolution of the Sorcery! engine, it’s much more than that, providing a singular, interactive literary experience that showcases inkle’s rare talent for pushing the envelope in showcasing new ways to relate to stories through digital media.

The best word I can use to describe 80 Days is elegant – from the interface to the music to the frequently compelling and faithful text, every element of this game works flawlessly to make you experience the immersive story and feel as if you are personally exploring its multitudinous assortment of exotic locales and destinations.

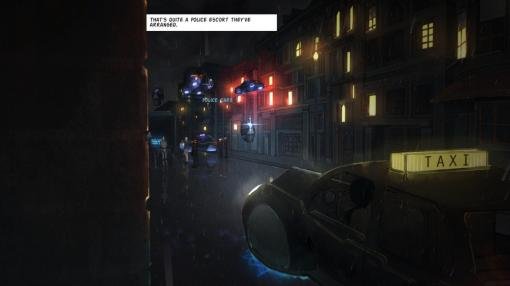

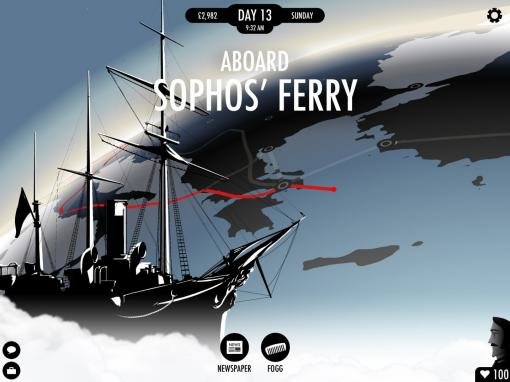

The game combines its wealth of text and sparse but evocative graphics very well. Each location has a number of icons (such as the bank or market) which correspond to your available actions and a silhouette that captures the spirit of the current city – if you decide to spend the night, a sun and moon will rise behind this silhouette to mark the passage of time. When it’s time to travel to your next destination, a global map appears and tracks your movement Indiana Jones-style across it. A stark black and white shadowed image of your current conveyance is also shown as you travel, illustrating the wealth of vehicular options at your disposal. Even the text itself, the main attraction of 80 Days, is attractively highlighted during your adventure, displaying white letters across a black canvas.

80 Days follows the basic plotline of Verne’s masterpiece: a British eccentric by the name of Phileas Fogg has accepted a bet that he cannot traverse the planet in 80 days. Like the novel, his journey to win that bet is aided and abetted by his French manservant, the properly appellated Passepartout. Unlike the original story, 80 Days is told in the first-person, and the player takes on the role of Passepartout, in charge of the major decisions for the duo’s jaunt across the globe.

In Sorcery!, you traveled from one definitive location to the next while making some minor choices (paralleling the Choose Your Own Adventure style of the original book) about which linear direction to take and how to overcome puzzles and obstacles at each location – which often used the original gamebook’s roleplaying mechanics to resolve. But 80 Days is tied only to the original narrative premise of Verne’s classic, and writer Meg Jayanth has taken advantage of this freedom by creating a larger world which stays (mostly) true to the spirit of the original.

There does need to be one word of caution here: Jayanth and inkle have taken one rather significant liberty with the original tale. Although Verne was also an accomplished science fiction writer of works such as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Journey to the Center of the Earth, Around the World in Eighty Days takes place very much in the world, time, and technological capabilities of the year (1873) in which it was written. The original Fogg and Passepartout traveled by train and boat on their trip. Jayanth has gone the steampunk route and allowed the pair to have access to steam-powered pneumatic horses, glimmering metal air carriages, and even trains which transform into submersibles. Although Verne’s own science fiction predictions became one of, if not the biggest, influences on the steampunk aesthetic, it’s a very steep departure from Around the World’s realism, and I still have a few reservations about it. Inevitably, it changes the journey from one that was originally intended as a showcase for the fantastical locations of our real world into one that is now actually just a fantasy. But as its own work, it’s absolutely engrossing.

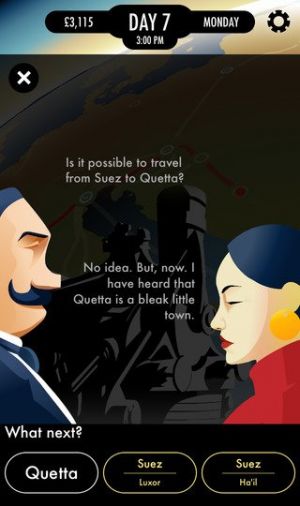

So how does 80 Days play? It’s a rather clever mix of gamebook, resource management, and open world exploration. After leaving your starting location of London for Paris, you must decide on each successive location that you will travel to – with a wary eye on the timer ticking down the 80 days you have to traverse the world and return in time to win Fogg’s bet.

The number of locations you can visit during play are astounding, and each offers new opportunities for adventures and mini-episodes that you can take part in or ignore as you (feel Passepartout would) see fit. Expanding on Verne’s 8 original destinations, Jayanth has provided over 150 locations to visit, from Sub-Saharan Africa to South America and even a number of American cities.

The number of locations you can visit during play are astounding, and each offers new opportunities for adventures and mini-episodes that you can take part in or ignore as you (feel Passepartout would) see fit. Expanding on Verne’s 8 original destinations, Jayanth has provided over 150 locations to visit, from Sub-Saharan Africa to South America and even a number of American cities.

At each location, you have a number of options available to you: you can visit the bank if the funds needed to book voyage have fallen low (such funds usually take a number of days to secure, which can stall your journey), explore the local area, visit the marketplace to purchase items for your limited inventory (which might prove fortuitous during your adventures) or maps to find new travel routes, and you can check the global map to begin planning the next leg of your travels.

Along the way, you’ll also need to manage the duo’s inventory and Fogg’s level of happiness. Some of the items you can buy at a market not only open new avenues of exploration or conversation options, but a train timetable might even provide new routes to travel when it’s time to disembark. However, each method of travel usually has a limit to how many items you can travel with (based on the number of “suitcases” allowed) unless you wish to pay more to get extra space (and cut into your finances). There’s also the option of selling items in your inventory to make a profit – an American outfit might be selling for pennies in Europe but worth serious dollars in the States – and keeping an ear out for tips on potential opportunities during your explorations can be profitable.

Keeping Fogg happy usually means playing a round of Whist or appealing to his creature comforts from time to time. He has a rating that begins at 100 but dips depending on the harshness of the traveling options you’ve chosen. It’s easy enough to take care of Fogg, but it usually means you have to decline exploring a city or having a conversation with another passenger. I didn’t find managing these resources particularly challenging – I never let Fogg dip below 80 (though I likely sacrificed a few adventures to do so) and at one point, I simply sold all of our current items to save on travel expenses, which didn’t seem to have much of an effect on our ability to make it back to London.

Exploring each destination in 80 Days is perhaps the greatest joy of the game, because each locale, whether exotic or familiar, usually offers a number of captivating characters, places to visit, and encounters that Passepartout can interact with. Mechanically, exploration is handled the same way as most gamebooks: you read the description of each location and are offered a handful of choices on how to proceed. Player agency is somewhat limited in the style of a gamebook, but often the choices are rather imaginative, allowing you to not only choose avenues to pursue, questions to ask, or actions to take, but might also determine how Passepartout even feels about an encounter, or flesh out the details of his own past, personal experiences.

The types of mini-adventures that Passepartout can take part in are equally imaginative. He might become embroiled in military actions in the Ukraine, visit marvelous scientific exhibitions at the World’s Fair, or become involved with a political uprising in South America. These episodes can range from the merely curious to complex and convoluted affairs, but each works to create an impressive sense of verisimilitude, and Jayanth’s rich text is very much responsible for making such a fantastical representation of this world feel so remarkably real.

Even after Fogg and Passepartout embark for their next destination, more unexpected events can occur en route. When you are in the middle of travel, you can elect to read the newspaper (which will often include mention of an event that you have been involved in or witnessed), converse with people on board your current conveyance or take care of your master’s needs. Often chatting with passengers can lead to new narrative opportunities. I met several fascinating characters whose familial backgrounds and stories provided even more depth, as well as chances to see if I could bring their personal stories to a satisfactory conclusion. Like many of the adventures throughout the game, I had mixed success – but I found that even if I wasn’t successful, these possibilities were just as enjoyable.

I’ll admit that I had such an anxious eye on the clock ticking down on my first playthrough that I visited only a fraction of the possible destinations, and experienced only a taste of all the adventures available. Meeting the deadline doesn’t seem particularly hard, however, as I was able to land back in London proper with 6 days and a lot of cash to spare. In many ways, that’s the point. The sense of wonder isn’t necessarily about reaching a final destination, but rather about the travel itself. After I had reached London again, I felt much poorer for the adventures I had missed – and promptly began a new journey to go back and see what I had missed. Indeed, 80 Days isn’t designed to be experienced only once, but rather as a puzzle box to return to and see what other possibilities are available. You won’t be able to reach every destination, or experience every adventure on every trip – meaning each journey is its own singular adventure.

I’ll admit that I had such an anxious eye on the clock ticking down on my first playthrough that I visited only a fraction of the possible destinations, and experienced only a taste of all the adventures available. Meeting the deadline doesn’t seem particularly hard, however, as I was able to land back in London proper with 6 days and a lot of cash to spare. In many ways, that’s the point. The sense of wonder isn’t necessarily about reaching a final destination, but rather about the travel itself. After I had reached London again, I felt much poorer for the adventures I had missed – and promptly began a new journey to go back and see what I had missed. Indeed, 80 Days isn’t designed to be experienced only once, but rather as a puzzle box to return to and see what other possibilities are available. You won’t be able to reach every destination, or experience every adventure on every trip – meaning each journey is its own singular adventure.

It’s also important to note that even if you do miss the deadline, the game doesn’t end. You can continue on your way home at your leisure, but you’ll have to contend with a very ornery Fogg, unhappy that you’ve lost his considerable bet. In addition, it’s been reported that there are a number of Easter eggs hidden throughout the game, as well as a number of “secret endings.” I haven’t found them yet, but I’ll keep looking.

That’s perhaps the most impressive success of 80 Days: that it succeeds not just as an enjoyable game of managing resources and decisions to reach a goal, but also as a fully accomplished story that offers multiple levels of excitement in revealing each layer of intrigue, exploit, and thematic element. It’s a game where a failure, either in reaching the meta-game goal or in bringing particular episodes to a satisfying resolution, is just as compelling and fun as each success. The adaptive story that you create is ultimately the most gratifying element of the game’s journey.

My only other complaint about the game is that the ending, despite all of the varied adventures I had taken part in, felt very anti-climactic. I wanted to know what happened to all the people I had encountered – and if my actions had had any effect on them or the world, but the game didn’t provide any insight, merely recounting the statistics (time and money spent) of my journey. This decision seems rather strange in a game so intent on delivering such strong and intriguing stories throughout.

Minor disappointments aside, every piece of interactive fiction aspires to produce the kind of experience that 80 Days has created so deftly – and so innovatively. The challenge of keeping text-based adventures viable, exciting, and accessible for a market used to the graphic eye candy of our new machines is no small feat, so it’s a welcome surprise that inkle have been so successful in adapting text adventures to our new mobile media. Their discovery of Jayanth is also a noteworthy achievement, as she is the muse who guides 80 Days as a revelatory work and a gripping, exhilarating experience. Available exclusively for iOS, this is a game that should not be missed by any interactive fiction fan.