Eye on iOS: Lost Phone edition

Eye On iOS

Our regular round-up of iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch adventure games

You’re walking down the street, minding your own business, when you spot a cell phone abandoned on the pavement. You look around, hoping to alert the owner. But no one’s around. What do you do?

This question is at the heart of not one but three recent mobile games that take very different approaches to the same dilemma. (All three of these games are also available for PC, but due to the phoney—ha!—nature of the gameplay, they’re a natural fit on mobile devices.) What can you learn about the person who lost this phone? Can you guess their passwords and figure out how to access protected files? How far are you willing to go to help out a stranger?

A Normal Lost Phone

In this $2.99 download from French developer Accidental Queens, the lost phone belongs to Sam, a high schooler struggling with identity issues. As you power up the phone, a series of increasingly concerned texts from Dad tip you off that Sam has just run out on his eighteenth birthday party, and his family is worried.

The user interface in A Normal Lost Phone is distinctly cartoony but the themes are grounded in reality, with Sam’s texts revealing a recent break-up, familial conflict over a gay cousin, and secrets Sam is keeping from his parents. A bit of digging through text, emails, and eventually profiles on an online dating site reveal that Sam is not the person his family and friends believe he is. If you liked teen-centric games like Gone Home and Life Is Strange, you’ll probably be drawn into Sam’s personal drama as well.

Sara Is Missing

In this free download from Kaigan Games, the lost phone belongs to a young woman who disappeared after a mysterious rendezvous a few nights earlier, and Siri is worried. Okay, it’s not Siri exactly, but this game gives you a digital personal assistant named IRIS to chat with, adding a dimension of interaction beyond simply snooping on someone’s lost phone. In Sara Is Missing, you aren’t only trying to find out what already happened, you immediately get mixed up in a story that’s still unfolding.

The interface is hyper-realistic, with photos, FMV, and virus-related performance issues seriously blurring the line between the real device you’re playing on and the fake one you’re playing with. Once again you’ll mainly piece together the story by exploring texts and apps on the phone, but here you must also share your findings with the AI by pressing your finger on details you think are relevant. You even need to make a few time-sensitive choices that impact Sara’s fate. The game is dark and at times gory, with a “found footage” vibe reminiscent of Lexis Numérique’s MISSING: Since January and the movie The Blair Witch Project.

Replica: A Little Temporary Safety

A $1.99 download from South Korean developer Somi, Replica is a bit different in that you haven’t found a lost phone—it’s been handed to you by a government agency digging for dirt on ordinary citizens. Here you play not as yourself but as Tom Ripley, a high school student detained by Homeland Security at some point before you (the player) jumped in. Find proof that the phone’s owner (a classmate imprisoned in the next cell) is involved in subversive anti-government activities, and in exchange Homeland Security will set you and your family free from detention.

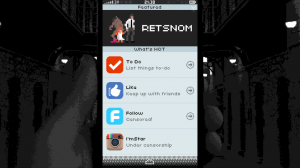

Replica’s interface is the least phone-like of the three games, with a chunky pixel art style reminiscent of the low-fi 1980s. I have no problem with pixel art in my adventure games (hey, I’m a child of the ’80s!), but I had a hard time wrapping my head around a smart phone interface that looks like an old Sierra game. It’s also hard on the eyes, which doesn’t bode well for a game that’s all reading. But the interface does make it absolutely clear that this is not the real world. It may remind you of another retro-styled, vaguely political game: Papers, Please.

These “lost phone” games understandably have gameplay elements in common. In all three, you’ll hack into password-protected apps, analyze personal photos, and try to gain access to protected files. You’ll even interact with the phone owner’s contacts, although the extent of this interaction varies a lot depending on the game. In A Normal Lost Phone, interaction is minimal because Sam’s phone doesn’t have any credits for making calls. In Sara Is Missing, you can “chat” with other characters at several points, but you do this by choosing among pre-determined lines, just like a dialogue tree in an adventure game, so it’s not truly a conversation. You do have the option to type responses, but if you don’t type the suggested words, the game overwrites your input with what it wants you to type, so there’s no freedom. Replica also includes text chats but these are totally scripted with no choice at all (think of them as text-based cutscenes).

While the phone-related gameplay seems clever and appropriate in isolation, playing these games in succession revealed a lot of overlap, such as passwords based on dates identified in the phones’ text messages and calendars. To be fair, anyone who owns a smart phone does the same basic activities with it, and it’s logical that the owners of these make-believe phones do the same sorts of things with theirs. But considering all three of these phone games start with essentially the same puzzle and the same solution, I have to wonder if this is a sustainable subgenre or a novelty that’s already wearing out its welcome.

It’s kind of fun at first, but at its core, gameplay that involves snooping through texts and guessing passwords is not all that compelling, especially when it’s so similar from one game to the next. That’s where the framing stories come in—the bigger picture narrative that motivates you to do all this digging. A Normal Lost Phone’s is very straightforward: a stranger dropped a phone and you picked it up. Nothing links you to the phone’s owner, and you can put it down again at any time. Your only motivation, therefore, is your desire to stick your nose in Sam’s business. Sara Is Missing gives you a more active role by suggesting that Sara will be harmed if you don’t figure out how to help her. And in Replica, you’re constantly reminded that your own freedom and wellbeing depends on how successful you are at hacking into your classmate’s phone.

|

A Normal Lost Phone |

I appreciated the framing stories in Sara Is Missing and Replica because they gave me a “good” reason to be nosing around in someone’s private information. ANLP is more problematic, because there’s really no excuse for poking around in a stranger’s phone to this extent. Of course, in adventure games we’re always reading notes meant for other people and pocketing items that don’t belong to us, so when I first played ANLP I didn’t think anything of hacking into the owner’s personal information. This phone was ostensibly left for me to find, so that makes it okay, right?

The problem is, ANLP has a very realistic depiction of a teen struggling with complicated questions of sexual identity—so realistic that the more I poked and prodded, the more uncomfortable I felt about my role in the violation. I remember chatting with Gone Home’s designer Steve Gaynor about the importance of the protagonist in that game being a family member rather than a detective. The Fullbright Company made that decision because a sister would have implicit permission to rifle through her parents’ papers and look in her sister’s closet. In A Normal Lost Phone, I’m the protagonist, and I do not have permission to look through Sam’s phone. Combined with the sensitive subject matter, this leaves me feeling conflicted about the game’s core premise and my involvement in it.

|

Sara Is Missing |

In Sara Is Missing, my “snooper’s remorse” was greatly minimized by the idea that I was helping someone in imminent danger. Still, a line is crossed when the perpetrator of that danger makes contact. (The right thing to do in this scenario, of course, would be to take the phone to the police!) As the stakes were raised, I was faced with a couple of uncomfortable choices underscored by graphic photographs of the people in danger. Because ANLP and Replica have stylized interfaces, I was always subconsciously aware that I was playing a game. But in Sara Is Missing—a game you play on your phone, tapping icons that look something like the icons on your phone, and seeing photographs of real people (actors, but still) suffering the violent consequences of your choices—it’s unsettling, to say the least. This is a horror game, and its slick presentation makes it very convincing. But while it may be effective, I wouldn’t call Sara Is Missing a fun experience. Even knowing I probably missed some of what this game has to offer, I was too disturbed by it to want to play a second time.

From a gameplay perspective, I enjoyed Replica the most of the three. I think that’s partly because by playing as someone who clearly wasn’t me, I could shrug off the guilt of messing around with someone else’s private information. That’s not to say that Replica is a guilt-free experience—it also involves some serious moral gray areas—but that’s the point of the story. Replica also has the most replay value, with up to 12 endings determined by how you use the phone. In addition to frequent text conversations to keep the pace moving, Replica includes a to-do list and your contact at Homeland Security feeds you hints. This sort of guidance would have come in handy in A Normal Lost Phone, where one password that didn’t follow the convention of the others had me completely stumped and unable to proceed until I checked a walkthrough. From looking at a Replica guide after I found a few endings on my own, I know that this game also has some “how on earth was I supposed to guess that?” puzzles, but at least those are optional, providing extra challenge for completionists instead of obstructing a first-time player’s progress.

|

Replica |

These aren’t the only games exploring how a phone interface can be used in interactive storytelling—the Lifeline series, the Mr. Robot mobile game (developed by the studio behind last year’s Oxenfree), and the WarGames-style KOMRAD are some others that I know of. While I enjoyed exploring A Normal Lost Phone, Sara Is Missing, and Replica, the gameplay does start to get repetitive. If you’re interested in the premise, my advice is to pick one with the story that most appeals to you instead of playing them all in a row. If this format is around to stay, then hopefully developers of future games will rely less on the reading of texts and cracking of passwords and start to come up with new ways to make the format engaging. Real-time, natural language chats with AI-driven characters would be really cool in this type of game. Just saying.