Puzzling (Mis)adventures: Volume 13: Where is My Heart?, Back to Bed

Puzzling (Mis)Adventures

Our regular round-up of puzzle-platformers and other puzzle-centric games

Whether first-person or third, adventure gamers are used to traditional perspectives, but some of the most devious puzzling can be accomplished by turning those perspectives on their heads – in some cases rather literally. Such is the case with Where is My Heart? and Back to Bed, the two latest puzzle-platformers in our ongoing cross-genre series. From navigating fragmented environments to walking on walls in a Dali-esque, surrealist world, there's much to enjoy here for puzzle-lovers who embrace a little sweat-inducing tension in their brain-bending challenges.

Where is My Heart?

Terms like “side-scroller” and “platformer” tend to conjure very specific images in gamers’ minds, priming us with learned expectations for how a title will look and play. It’s easy to take these terms for granted because the challenge is usually in the gameplay itself, whether solving puzzles, avoiding traps, or shooting enemies. But what if the challenge also (or even primarily) comes from an attempt to break those preconceived notions of how a game’s levels or environment are “supposed” to be displayed onscreen?

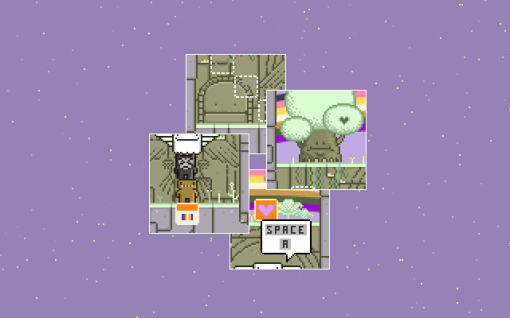

Enter Danish developer Die Gute Fabrik and Where is my Heart?, a very conventional, if stylish, 2D platforming experience freshened up with a very clever twist—not on the genre itself, but in how it is presented. Each level has been chopped up into a multitude of small rectangular tiles, and then shuffled around, and the disorienting results are similar to a jigsaw puzzle with its pieces out of place. This deceptively simple change in perspective forces you to come to grips with the spatial relationship between each frame, essentially piecing the level together mentally in order to understand how to guide the protagonists across the fractured landscape.

Topping even the quirky, attractive aesthetics, the main attraction here is all about how altering the presentation can create a challenge in what would otherwise be typical (and, for most players, fairly easy) platforming gameplay. Indeed, all the components of an old-school platformer are to be found in Where is my Heart?, such as deathtraps that require precise timing in order to dodge, blocks that are activated with a head-bump, and collectable objects scattered around the level. I think I can safely say that gamers put off by platforming games in general, or those who lack quick reflexes, will find no respite here, though the opportunity to experience something that, to my knowledge, hasn’t been done before, could make it worth a look even by those who would otherwise be uninterested.

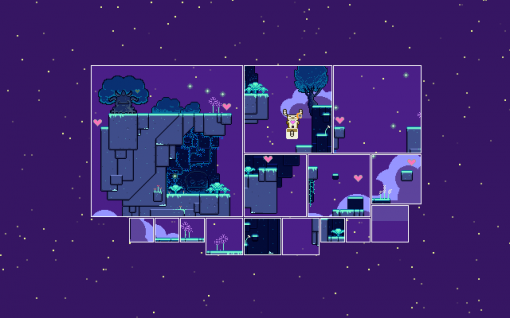

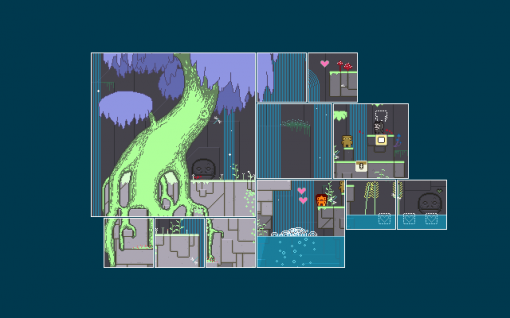

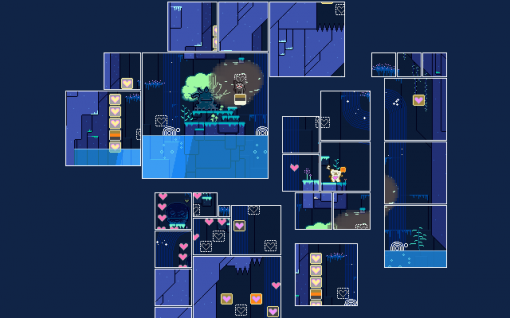

Each of the game’s twenty-six discrete levels (three additional levels are unlockable on PC after the credits roll) displays gorgeous, near-psychedelic visuals. The colors are especially unusual and bright, owing to the pastel hues, and the crisp pixel art could best be described as “cute.” Although forest is the predominate backdrop early on, later environments include such features as burbling blue waterfalls, twinkling stars, and creepy caves. Vegetation even reacts to your actions, such as small mushrooms that shrink into the earth when passing by them, only to pop back up a moment later, and fields of grass that bend as the characters walk through them. Nighttime environments are a special treat, the color palette taking on vivid neon hues that are a delight to behold. In many ways it’s a shame that the visuals are obfuscated throughout much of the game, even if it is necessary to accommodate the fragmented presentation that makes up the bulk of the “puzzle” part of the puzzle-platforming.

Sound effects are excellent, too, and fit in with the whimsical, dreamlike atmosphere. Bird calls echo through the forest, the sound of water trickles down walls, and even the gentle tap of a character’s feet hitting the ground after a jump imbue each level with life. The music is another well-designed feature, though the surreal, downtempo melodies of the chip-tune soundtrack tended to annoy me at times. However, it works very well with the aesthetic of the game, so whether one likes it primarily comes down to taste rather than technical execution. Luckily, the music tends to fade in and out depending on the events taking place onscreen, rather than being an ever-present distraction.

The game begins much like any other platformer, introducing a family of monsters named Grey (the father), Orange (the mother), and Brown (their son). The premise involves the trio searching for the Heart Tree, a large anthropomorphic tree that, as a result of a tragic mistake by the monsters, floats away at the end of the first level, leaving a fractured world in his wake. I initially had high hopes for Where is my Heart?’s story, particularly because the trailers I had seen suggested unsettling, almost sinister tones beneath its cotton-candy exterior, and the colorful environment in which the game is set seems ripe for bizarre happenings. However, other than the overarching “Find the Heart Tree” objective to provide rudimentary motivation, the story is abstract and left largely to the player to interpret.

To help in this regard, the protagonists are given their own distinct personalities, revealed in unvoiced quotes displayed before the start of each level, and in the idle animations seen occasionally during gameplay, such as when Orange weeps softly or Grey grumbles in frustration. In addition, each character is able to transform into a forest spirit, an alter ego of sorts which gives each one special abilities, such as Brown’s “Antler Ancestor,” who can double jump and is followed around by “The Fireflies” (actually diminutive versions of his mother and father), Orange’s “Rainbow Spirit of True Sorrow,” a smiling, angelic creature who can shift the game’s panels around, and Grey’s “Bat King,” who can reveal hidden routes and platforms. A few quotes from the alter egos suggest that they are, in fact, meant to represent repressed desires or fears that strain the characters’ relationships with one another, but while the quotes are occasionally unsettling (such as Orange’s “Make one mistake in life and it will never be forgiven,” or my personal favorite, the Fireflies’ “We love to cause mutual trauma”), and they do flesh out the characters somewhat, the story never feels particularly deep or truly integral to the gameplay.

The main goal in each level is simple: gain access to the exit located somewhere out of immediate reach. Like the entry point, the exit features a whimsical face, either engraved upon a stone or etched into the trunk of a tree, which opens its mouth to let the characters through once they reach it. Although it is easy to see the exit, getting to it is the challenging part, owing to the fractured, jumbled nature of the presentation. In order to successfully navigate the environment and reach the door, players must explore the relationship between the various tiles, using such clues as watching a cloud passing by in several frames at once, or walking a character to the edge of a tile to see which of the other panels it leads to. Of course, jumping onto platforms and avoiding traps along the way, such as spike-pits or bottomless chasms, provides even more challenge, often because you only have a general idea of where the trap is located in relation to the characters until further exploration reveals more clues. Luckily, the keyboard-centric controls are easy to grasp, in which the arrow keys move the characters around, the spacebar is used for jumping, and the ‘D’ key is used to switch between the protagonists. For the most part, difficulties come from the obstacles and the disorienting layout, not the controls.

Typical tasks needed to get all three characters to the exit include standing on each other’s shoulders in order to reach higher ground, leaping across chasms, or activating interactive blocks to unleash a flurry of pink hearts that create new platforms to aid the protagonists or remove existing blocks that impede progress. At times, it is impossible to gain access to parts of the level through any conventional means, perhaps because the height of the platform is prohibitive or is hidden behind a wall. In these cases, you must use a character’s alter ego to perform actions not normally possible with that character’s basic form. Although the Antler Ancestor and the Bat King are fairly straightforward, Rainbow Spirit is somewhat more complex (but also quite useful), in that she can reposition the tiles onscreen, providing spatial clues that aid navigation. She can also shift her presence between tiles as they rotate, allowing her to gain access to areas of the game that are otherwise not directly accessible. Her abilities are also helpful in the few situations where only partially-visible tiles can be brought fully into view.

While the gameplay is quite polished, the greatest criticism I noted is how repetitive the action becomes after a while. With no story, per se, to motivate my actions and keep me intrigued, there were only so many jumps, double jumps, and character transformations that I could perform before feeling like I was simply doing the same thing over and over again. Even with the characters’ special abilities to provide some spice, most of the gameplay is a variation on those three actions. What mitigates this issue somewhat is the fact that levels unlock in a staggered fashion, typically revealing two new levels for every one completed, so that if you get stuck on one level, you can switch to another one.

The potentially-quite-brief playtime also prevents the game from truly wearing out its welcome. Gamers with quick reflexes who have little difficulty mastering all that the game has to offer, could finish in a matter of 2-3 hours, though my own experience suggests an average of about 3-5 hours, plus more if an optional secondary objective is followed through to completion. For me, the game was over before things got too repetitive, though the anti-climactic ending did elicit a verbal “is that it?” when the playable credit sequence began, leaving me ultimately underwhelmed. The three bonus levels available after finishing the game on PC actually do have a bit of variation in them, but they generally feel experimental and unpolished compared to the rest of the game.

It is possible to die in Where is my Heart?, and it is intended to be part of the game, since at times, despite your best efforts to understand the layout, blind jumps are required in order to ascertain exactly how to proceed, leading to death for the character in question if they are unfortunate enough to land on a spike or in a pool of water. In cases like this, the punishment is a return for that character to the door in which they entered the level. While trying to master leaps that require precise timing to avoid hazards, having to repeatedly traverse areas of the level that I had already solved, only to fail the jump again (and again...and again...) and have to repeat the process became frustrating and tiresome. Luckily, this specific issue only raised its head once or twice.

In addition to the main objective, you can collect a number of pink-colored hearts scattered around each level. Once collected, a heart floats over to the exit door which consumes it, gradually illuminating a small heart-shaped icon set in the outer edge of the door. When a character dies, however, a black heart floats up from where they met their end and the door consumes it instead, turning the icon dark. In addition, the door’s facial expression gradually changes as hearts of both colors are collected, with pink hearts giving it a joyful grin, and black hearts eliciting a morose frown.

Given the obvious effects, initially I thought that perhaps a certain number of hearts would have to be collected in order to leave the level, but the purpose of the hearts has minimal bearing on gameplay, seeming to be little more than a “gotta get ‘em all” collect-quest for completists. Even after collecting no hearts or dying numerous times in one level, I could pass through to the next level with no apparent ill effects on my progress or the characters, although the “score” metric on the level selection menu showed that collecting black hearts reduces the final score for that level.

Despite how complex Where is my Heart? might seem in concept, underneath the unique layout disorientation lies a very competent and traditional platformer, in the same vein as Super Mario or Kirby’s Dreamland, only without enemies to fight and with a more puzzle-oriented design. During my time with it, what surprised me most of all is how a simple change in perspective turned what would have been a fairly easy game into a brain-bending experience.

I also found it interesting how the perspective actually made full immersion in the game’s colorful world a detriment to progress. “Immersion” is typically one of the prime goals for any developer. However, in order to navigate each level I had to keep a mental arms-length from what was happening onscreen so that I could watch for clues on how to proceed. Getting too involved often meant inadvertently passing over to an adjacent tile and falling into some trap I wasn’t expecting. Creating an experiment in “anti-immersion” may not have been the developer’s intention, but it was a rather fascinating side effect of the game’s unique viewpoint. The story in Where is my Heart? could use some work, as it was a bit too vague for my taste, but Die Gute Fabrik’s experimental take on the typical puzzle-platformer, backed up by quirky, beautiful pixel art and excellent sound effects, likely makes it worth a look even by those who don’t normally find themselves attracted to these kinds of games.

Back to Bed

Although the term "surreal" tends to be used quite a bit when discussing video games, Surrealism – the art movement exemplified by Salvador Dali – doesn't have as much representation, and I've always thought that to be a missed opportunity. There's just something about the strange, often unsettling nature of Surrealist works that seems perfect for exploration through an interactive medium, and developer Bedtime Digital Games seeks to take advantage of that fact with their 3D puzzler Back to Bed. The unique Dali-esque design is overshadowed by a lack of variety and ambition across the entire game, but the art makes a good first impression and there is some puzzling fun at times.

Only the most threadbare of narratives (a basic premise, really) ties the game's thirty levels together, "told" through a few crisply-drawn, Art Deco-style animation sequences that appear between certain levels: Bob, the main character, has narcolepsy and suffers from severe bouts of sleepwalking. He often falls asleep at unfortunate moments, such as while at work in his high-rise office building. While unconscious, he takes a stroll across rooftops and other hazardous environments, his dreaming mind transforming ordinary places into strange and unsettling locales, populated by enemies like nightmarish dogs, trains that take the form of giant whales, and anthropomorphic alarm clocks that threaten to wake him up.

The player's main task is to guide Bob, who ambles slowly through each level with arms outstretched, back to the safety of his bed, navigating the terrain and avoiding various hazards and enemies along the way. But there's a catch: you can't control him directly. Instead, you take control of Subob, a green dog-like manifestation of Bob's subconscious mind, who serves as a dream-guide of sorts. The first few levels form a brief tutorial, introducing the concepts needed to master the challenges ahead, such as how to navigate Subob around, pick up and place objects, and how to lead Bob back to his bed, usually located in a spot that looks deceptively accessible from where our sleepy protagonist quite literally drops into the level. The maze-like environments are clearly inspired by the optical illusion-based works of M. C. Escher, and include things like stairs that lead to traversable walls (often containing an object that the player must retrieve), floors that seem to intersect with higher ground, and even portals that allow the player (and Bob) to go from one place to another in an instant.

Much of the game's challenge comes from having to analyse and solve each level in real time, modifying Bob's course just in time to save him from falling into the void or encountering an enemy, using moveable obstacles scattered throughout the environment. These include giant green apples (a sly reference to artist René Magritte) and, in later levels, fish-shaped bridges that allow you access to areas that would otherwise be off-limits. Such objects must be used in conjunction with fixed obstacles scattered around each level, such as walls and chimneys that cause Bob to turn, and air vents that push Bob off course.

Bob himself also has a hand in making life difficult, because he can only make right turns after coming into contact with an obstacle. The effect of this limitation is that the most simplistic level often requires a circuitous solution. For example, one level begins with Bob only a short distance away from his bed, but facing away from it. In order to solve the level, you must deduce how to successfully turn Bob 180 degrees, filtering out misleading environmental clues and items that appear to be part of the solution, but ultimately have no purpose other than set decoration. As Bob walks forward, his expected path is displayed as a series of footsteps on the ground, which helps the player determine where Bob is headed, including any turns he might make along the way.

There is a pause function for when you need to take a break, but the camera, which displays each level from an isometric perspective, cannot be moved around while pausing, preventing players from "cheating" and inspecting the level without risking Bob's safety (if such a thing could, in fact, be called cheating). Since timing is an important element when solving many of the puzzles, anyone who is particularly averse to timed sequences would also be advised to avoid Back to Bed. Most players, however, should be fine.

Bob met his “demise” far more times than I could count during my playthrough, but it’s worth noting that there are actually two different types of failure that you can encounter. Falling off a ledge only results in Bob returning back to the beginning of the level. Depending on the solution required for that puzzle, you may have to backtrack in order to guide Bob back to the point where he fell, but otherwise the level continues on. However, when Bob is woken up, such as when he encounters an enemy, the game immediately ends, bringing up a screen where you can choose to either restart the level or return to the main menu. While this difference might seem like an arbitrary (and occasionally frustrating) distinction, it does raise the stakes for certain actions, such as when Bob crosses through an area filled with enemies.

Despite Bob's ambling pace, there are times when the game becomes a tense scramble to ensure that all the objects are placed properly, especially when you only have one apple and have to follow Bob through a tight, obstacle-laden area to keep him on track. Even so, I hate to say that I eventually succumbed to boredom. The game is split into two fifteen-level sections, the first half consisting of a cityscape theme and the back half featuring a nautical motif, with new obstacles (such as the air vents) added throughout. However, despite the increasing complexity of the levels, there are only two that ever gave me any real challenge at all. In fact, the entire first half on city rooftops is so breezy that it feels like an extended tutorial, and the difficulty really doesn’t raise significantly even after that point. By the end, the fun had worn off and I was just going through the motions in order to finish the game.

There are glimpses of what could have been, though. The final level toys with a mechanic using an optical illusion based on the camera's isometric perspective. It isn’t really complicated at all, but it is one of the few puzzles that had me scratching my head for a solution, and actually is quite satisfying to solve, mainly because it utilizes the Escherian aspects of the level design to a greater extent, and in a far cleverer way, than in all the previous levels. Based on this experience, it is clear that Back to Bed could have been a much more varied, innovative game, and I have to wonder why more of these kinds of puzzles were not included. Whatever the reason, the presence of just the one reinforces how incomplete the gameplay feels when taken as a whole.

My initial playthrough lasted around 2½ hours, after which there was an opportunity to experience "nightmare mode." Anyone expecting new levels, or even the same levels with more obstacles and traps (something that would have actually been worth the time to check out) will be disappointed. Instead, nightmare mode consists of the same levels, but this time the door that Bob's bed always sits behind is locked, so you must retrieve a key placed somewhere in the level. Obviously, this allows for a longer experience, but I just don't see it being something most players will be interested in, other than perhaps hardcore completists and those who really want to squeeze all the puzzling they can out of the game. Honestly, for whatever amount of trouble the developers went to in order to include this mode, I would much rather have seen a more varied core set of levels.

You have a choice of controlling the game using a gamepad or mouse. If using the mouse, holding the left button down and moving the mouse in a given direction allows you to move Subob around, and right-clicking when adjacent to (and pointing the cursor at) an object allows Subob to pick it up and set it down again. Both controller options are viable, although they can also be frustrating during sequences that require quick timing. The ground is shaded in alternating light and dark squares, much like a checkerboard, and each square corresponds to valid locations for object placement, lighting up when carrying an object over it to show that it may be placed there. More than a few times, however, I picked up an object and ran to place it in front of Bob before he fell into the void, only to have the highlighted square change abruptly. This resulted in placing the object down on the square next to the intended one and watching helplessly as Bob trudged right on toward his demise, with no time to fix the mistake. The issue does not seem to be a bug, but instead a symptom of the picky placement grid tolerance. Fortunately, this issue doesn't raise its head too often.

Much of my initial interest in Back to Bed came from the prospect of seeing how the classic themes of Surrealism, like melting clocks and barren landscapes filled with strange creatures, might translate to an interactive medium, and in many ways the artists have succeeded in bringing this distinct vision to video game form. Each of the game's thirty levels feels as though it could have been painted by Dali himself, with earth tones like pale orange, brown, and tan accompanying more vivid hues like greens and blues. The cutscenes that play between certain levels have an ominous tone to them, owing mostly to the music. They are interesting for their clean, hand-drawn illustrations, and they are the sole attempt to give the game a narrative, but they lack the depth or the time needed to do so. In any case, they work well as transition animations between the two sets of levels, and as beginning and ending cutscenes.

The cityscape levels and harbor levels are largely similar. The former has chimneys and walls atop tall buildings that crumble away into the void, and the arrival of the harbor motif causes the scenery to change accordingly. It’s mainly superficial, however: in place of chimneys there are smokestacks; instead of windows on the sides of buildings, clamshells and lifesaver rings dot the terrain. Plenty of strange sights can be found across both themes, including creatures such as winged chess pieces, bowler hats that squawk as they fly through the air, and clocks that run backwards. Disembodied eyes peer from behind window shutters and from inside clamshells, the latter reminiscent of pearls. Fanged dogs and anthropomorphic alarm clocks roam many of the levels, and other creatures are just as bizarre, such as trains that appear as giant whales, and traps in the floor that take the form of hungry, long-toothed maws.

At first, the sheer pleasure of seeing such unusual images is a treat. You are faced with a veritable avalanche of Surrealist tropes (yes, animated melting clocks do make an appearance, and yes, they are hypnotic) that make references to several renowned works and their artists, and multiple times it felt as though I were truly exploring a moving Dali painting. Yet after this strong initial impression, I eventually became dissatisfied with the graphics. Only a few levels in, I was struck by how similar everything looked and felt, and it only got more repetitive from there. It's not that the art style itself becomes stale; it's that there isn't a whole lot of variety to give it substance. The same environmental assets are reused over and over again with no change in color or appearance. Even when the game switches from the cityscape to the nautical theme, there’s simply not much difference between the two, aside from simple cosmetic changes, echoing the same problem with the gameplay mechanics.

Sound effects comprise one area where the game performs fairly well. Subob makes a skittering noise as he walks, and Bob's footsteps can be heard making a light plodding sound. Other effects, like Bob's bedroom door and the various creatures inhabiting each level are nicely atmospheric. Bob snores throughout the game, which can be a bit grating, but it is quiet enough that it doesn't become too bothersome. An auditory highlight comes in the form of the disembodied, distorted male voice that narrates the tutorial and continues to chime in periodically to comment on things happening onscreen. His nonsensical musings are quite comical ("The apple is a hat," he says at one point, while Subob carries an apple over his head), and they constitute one of the few things that I can praise without qualifications.

The music is dreamy and downtempo, but like almost every other part of Back to Bed, it feels woefully underdeveloped. There are only a few tracks, and it sounds as though only one of those is used as background music, though the tunes are so similar to each other that I was never certain if that was actually the case. There is definitely a different score for the cutscenes, which is appreciated, but it's baffling that with so few tracks, the developers didn't make all the music available as background music for the levels.

The thing that most stands out about my experience with Back to Bed is its lack of ambition. There are so many times that the game could have done something more compelling, whether through gameplay, art style, or music, but instead opts to go only halfway, shooting below a target that wasn't really all that high to begin with. There is some fun to be had with the puzzling gameplay, but it quickly succumbs to the same lack of initiative and variety that affects the rest of the game, leaving you to go through the motions of solving numerous iterations of the same puzzle. As excited as I was to see a Surrealist interpretation alongside an equally-promising Escher-inspired level design, this game let me down. It's not a "bad" game as much as it is an incredibly (and at times, bafflingly) mediocre production that never aspires to be more, even when there are obvious opportunities to do so. There are better puzzle games out there, and at least for now, Salvador Dali is still the undisputed master of Surrealism.