GDC 2014 - LucasArts Post-Mortem

“Stay small. Be the best. Don’t lose any money.” – George Lucas’s original directive to the team of Lucasfilm Games

In providing a forum to discuss the design, philosophy, ambitions and future of interactive storytelling, the Game Developers’ Conference (GDC) has hosted a number of post-mortems for computer games throughout its more than 25-year history. At GDC 2014, however, the conference held its first ever post-mortem dedicated to the story of an entire studio. In this case, it examined the rise and fall of one of the great adventure gaming companies of the 1990s, Lucasfilm Games (which became LucasArts in 1990).

|

Noah Falstein |

The post-mortem was moderated by Noah Falstein, who was one of the first designers that George Lucas tapped to begin a games division under the rapidly expanding Lucasfilm empire of the early 1980s. Falstein performed his duties wearing Google Glass, a nod to his most recent employment as chief game designer for Google. He opened the session by asking how many people had ever played a LucasArts game. Nearly everyone in the audience clapped or raised a hand. Joining him on the panel were fellow Lucasfilm Games alumni Steve Arnold, Peter Langston, David Fox, and Chip Morningstar, as well as adventure gaming legend Ron Gilbert.

More than just a nostalgic journey through the company’s past, the post-mortem also provided a compelling analysis of what made it possible for the company to take so many chances while creating a corporate community that nurtured innovation and creativity. (Although the panel was a little rose-colored about the studio’s history: the company’s eventual downfall and dissolution, and the reasons behind it, were barely mentioned.)

|

Lucasfilm / LucasArts logos over the years

|

Lucasfilm Games was initially conceived as a method to avoid the tax penalties incurred from the runaway commercial success of George Lucas’s film franchises – most notably Star Wars and Indiana Jones. Lucas could avoid the fees by reinvesting in his own company, so he created a computer division of Lucasfilm. After the release of the final film of the original Star Wars trilogy, Return of the Jedi in 1983, Lucas directed the computer division to explore what he believed could be a revolutionary creative field: computer gaming. His first decision was to hire Langston to recruit and manage a new team of gaming pioneers. “I wanted to create an environment that allowed and encouraged creativity, not marketing deadlines,” said Langston. “I tried to manage the group as a group of peers.”

Lucasfilm’s initial games, designed for Atari’s primitive 800 and 5200 computer systems, may seem crude by today’s standards – it wasn’t until much later that they would create classic adventure games for personal computers – but they did provide several interesting historical technical and aesthetic innovations. Langston himself wrote the music for 1984’s Ballblazer, which featured an improvisational musical algorithm designed to give context to what was happening during the frenetic arcade game’s play. Another game, Rescue on Fractalus! (1984), featured a fractally-generated alien landscape for the player to fly over in a spaceship (as well as one of the very first surprise twists in a game).

|

Peter Langston. Photo by Rick Browne / Picture Group for San Jose Mercury News,

|

After bringing in Langston and committing resources to the division, Lucas’s direct involvement with the company was minimal. “The joke with George was that when we were presenting to him… he would look at something and consider it very deeply and say ‘great!’ and that was it,” said Arnold, who was poached directly from Atari by Langston. “Getting a ‘great’ was a good outcome when you were presenting to George.”

Beyond providing the brief philosophical edict quoted above, Lucas had only established one more rule for the new team. They were forbidden to use any of the film division’s artistic properties. “We were told right up front that we were not allowed to do Star Wars titles,” said Fox, one of the team’s first full-time game designers. “I was really upset – I had joined the company because I wanted to be in Star Wars.”

This restriction, however, was cited by the panel as one of the main reasons for Lucasfilm Games’s early creative success. The limitation forced the young team to create entirely new worlds from scratch that weren’t bound to existing narrative canon or physical rules. “We were creating a culture that was designed around innovation… We had the brand of Star Wars, the credibility of Star Wars, and the franchise of Star Wars, but we didn’t have to play in that universe. We were a group that lived inside a super-creative, technologically astute company and we got to do our own invention… We got to make up our own stories and call them Lucasfilm,” said Arnold.

|

The team on the cover of Atari Connection, Spring 1984. (L-R) David Levine, Peter Langston, Gary Winnick, David Fox and Charlie Kellner. Click to view the full cover.

|

Interestingly enough, the direction to create new IPs also caused some tension within the company itself. “Unbeknownst to me at the time, it [the freedom] turned out to be the source of a lot of jealousy in other parts of the company, because here we were getting to create our own stuff, and all of these other really creative, really capable people were forced to march to George’s vision,” said Morningstar.

The panel likened the experience of working for Lucasfilm Games during the early days to a contemporary independent game or film company. The videogame industry was still in its infancy, and the rigidity of catering to market projections and demographic metrics was still years away, which allowed the game designers a singular opportunity for playful experimentation. “We were really driving towards trying to figure out how we could we take this franchise that people associated with George and Lucasfilm, which was innovative storytelling, and apply it to this new interactive world. We invented lots of different things because we had permission to do that,” said Arnold.

|

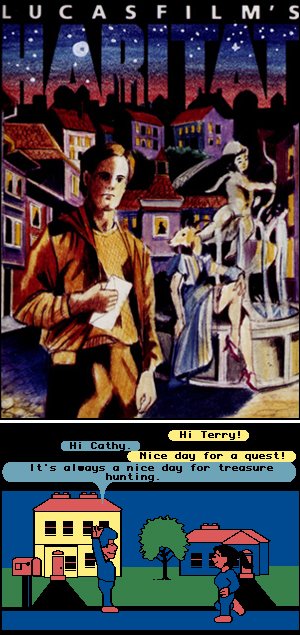

Perhaps one of the most interesting (if potentially ill-fated) experiments by Lucasfilm Games was Habitat, conceived before the term Massively Multiplayer Online game (or MMO) had even been invented. Predating Linden Lab’s Second Life by decades, Habitat allowed players to connect their computers, such as the popular Commodore 64, through the era’s primitive modems to a virtual cartoon space that they could explore with other users. A product well ahead of its time, Habitat was one of the company’s few early commercial failures, although it is still lauded for its extraordinary ambition. (The idea of pushing such large quantities of data through 300 baud modems had been previously considered a nearly heretical impossibility.) “We didn’t know you couldn’t do that, so we just went and did it, and it worked!” said Morningstar, one of Habitat’s designers who even helped coin the now-ubiquitous term “avatar” for players in the game’s virtual playground.

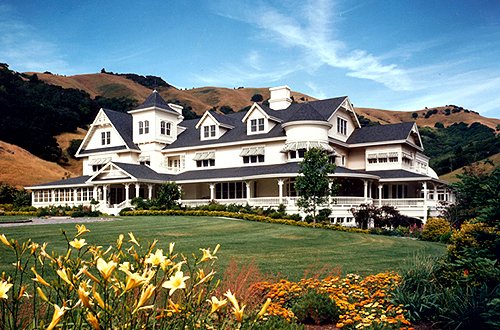

As the Lucasfilm Games team grew, new opportunities for collaboration grew as well. The young team even created a new word, “funitivity,” over many of their shared meetings (and frequent lunches at Skywalker Ranch, located just north of San Francisco in the idyllic headlands of Marin County) as a concept to determine if a proposed project was worth pursuing. A new game may be fun for the designer, but would it be fun for an audience? Perhaps the game that benefitted the most from this spirit of cooperation was the first game that Lucasfilm Games published in-house, and their first true adventure, Gilbert’s and Gary Winnick’s Maniac Mansion.

|

Maniac Mansion's design was inspired by the Main House at the Skywalker Ranch

|

Maniac Mansion’s greatest technical innovation was the SCUMM engine, which provided a more accessible method of interaction for adventure games than the text parser that was standard in Sierra On-Line’s extremely popular, and profitable, adventure games. “My biggest memory of Maniac Mansion was almost being fired… because the code was going nowhere,” said Gilbert. “Chip had suggested why don’t you do a scripting language… it all seemed crazy to me on a Commodore 64. Chip actually convinced me it would be doable and then went out and wrote the first SCUMM compiler over lunch, which was very impressive. From that came this whole adventure game scripting language which obviously went on to power most of the Lucasfilm adventures: Maniac Mansion, Zak McKracken, and Monkey Island and Sam & Max and all those games. It was the environment we had. Everyone worked together.”

|

Inside the Maniac Mansion

|

Shortly after the SCUMM engine debuted in Maniac Mansion, followed by 1988’s Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, the gaming division’s restriction from using Lucasfilm IPs was finally lifted. This new freedom allowed for the creation of two adventure classics in Lucas’s lucrative Indiana Jones universe: the adventure game adaption of the Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade movie and the original Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis. Falstein served as co-designer for both games.

|

Sophia Hapgood and Indiana Jones investigating the fate of Atlantis

|

In 1990, Lucasfilm Games became LucasArts, and their adventure game successes became legion. The quality of LucasArts adventures, from Infocom luminary Brian Moriarty’s Loom to Gilbert’s own Monkey Island series, began to surpass even Sierra’s formidable catalog even if they never reached the same commercial heights. During the Q&A session, Gilbert was asked directly about how the rivalry between the two companies affected LucasArts. “They sold so much better than we did,” Gilbert replied. “King’s Quest sold maybe ten times what Maniac Mansion did. There was always this competition to do better than them, although it was all friendly. We actually had a baseball game with them at the ranch – which they won. Their success really drove us to do better.”

Another adventure fan in the audience commended Gilbert on the humor in the LucasArts adventures and inquired why it had been so essential in each release. “I think humor is really important in adventure games because you’re doing completely ridiculous things. It helps if you can poke fun at those things. If you’re doing a game that’s a comedy, you can have a rubber chicken with a pulley in the middle and no one really questions that. If you’re doing a serious game, and you have something strange, there’s a suspension of disbelief that’s lost,” Gilbert said. Falstein recalled how the infamous rubber chicken was simply the result of a brainstorming session with The Secret of Monkey Island design team. The absurdity of the rubber chicken’s eventual use as a transportation device had brought so much laughter to the LucasArts team that it was apparent it needed to be included in the actual game.

|

Ron Gilbert in the '90s; sage advice from Guybrush in The Secret of Monkey Island

|

“The big thing that was special was that we had the support of the entire Lucasfilm team,” said Fox. “When we had a game concept it was passed around by all the other designers. I haven’t seen that many other places, that feeling of support from everyone.”

|

Apocryphally, the pinnacle of LucasArts’ artistic success is often considered the end of the 1990s “golden age” of adventure gaming. LucasArts wunderkind Tim Schafer’s Grim Fandango, a critical darling commonly listed as one of the greatest adventure games of all time, was publicly perceived as a disappointing commercial failure – perhaps unfairly, as it continued to sell decently in the years that followed, but perception often becomes reality.

As the gaming industry had grown increasingly more lucrative, crowded and turbulent, LucasArts began to turn away from its experimental roots to focus almost exclusively on “safer” commercial ventures – usually based around cashing in on the Star Wars license. The company released first-person shooters, real-time strategy games, and even an MMO. (The film studio followed suit by releasing an equally uninspired prequel trilogy.)

The GDC panel did not dwell on the reasons for the company’s eventual collapse (all game development halted for good in early 2013), perhaps because they had all long since moved on to other ventures by then, and instead they concluded by discussing what made Lucasfilm Games such a singular place for creativity during the ‘80s and ‘90s – and whether another company might be able to capture a similar magic.

“One of the benefits we had was that we got to adopt this indie spirit,” Arnold said. “We got to push ourselves to figure out what was interesting or what was fun or what was creative… One of the questions I would have for the companies of today is whether or not there is room for that kind of innovation. Try something new rather than do something bigger, harder, and faster that we’ve already done a bunch of times… We had the chance to say we think we can do this; we actually don’t know if we can, but if we could, it would be worth it.”

On that note, the panel’s eloquent and melancholic eulogy for the company they built proved how worthwhile pushing beyond the boundaries of expectation in art, expression, and “funitivity” can be.

R.I.P. LucasArts.