Puzzling (Mis)adventures: Volume 8 - Nihilumbra, Grimind page 2

Puzzling (Mis)Adventures

Our regular round-up of puzzle-platformers and other puzzle-centric games

Where would adventure games be without puzzles that cause us to strap our thinking helmets on tight and their oftentimes gripping, emotive narratives that let us identify with heroes and villains alike? These elements aren't the exclusive domain of adventures, though, as sometimes familiar things can be found in unexpected places. In this edition of Puzzling (mis)adventures, we take a look at Nihilumbra and Grimind, two games that marry traditional adventure stories with bleak settings that require you to have your platforming shoes firmly strapped in place.

Nihilumbra

It can be tricky to define what exactly constitutes an adventure game. A heavy focus on plot, inventory-based puzzles and the occasional point-and-click interface are all hallmarks of the genre, and will instantly place a game within its ranks. But sometimes the lines get blurred. What degree of storytelling must be present for a game to qualify as an adventure? Where do we draw the fine line between a puzzle game with a few action elements and an action game featuring puzzle elements?

Beautifun Games’ Nihilumbra is a game that straddles the fence between being an environment puzzler/lite adventure and a narrative-centric platformer, but ultimately falls more into the latter camp. Clearly taking cues from such other kissing cousins of the genre as Limbo and Lucidity, Nihilumbra serves up a stark and lonely tale of existentialist guilt and one creature’s irrepressible will to live, set in a bleak yet beautifully simplistic landscape.

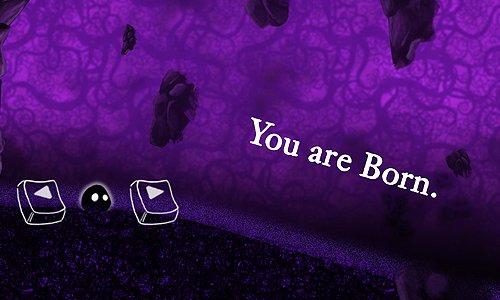

Nihilumbra’s reluctant protagonist, aptly named Born, was literally born of the Void – an all-consuming nothingness intent on swallowing up all of existence. At first he is nothing more than a shapeless blob ejected from the Void, with no past or future, no apparent soul. Aimlessly crawling along, he soon takes on humanoid form, assuming the shape of a scarecrow glimpsed along the way. Perhaps sensing a familiarity and comfort with this shape, Born’s observations of the terrible loneliness and intense beauty of his surroundings cause him to grow increasingly attached to the world he passes through. Ultimately, however, in the process of defying the Void as it attempts to reclaim him, he brings ruin upon all he visits as it chases him relentlessly.

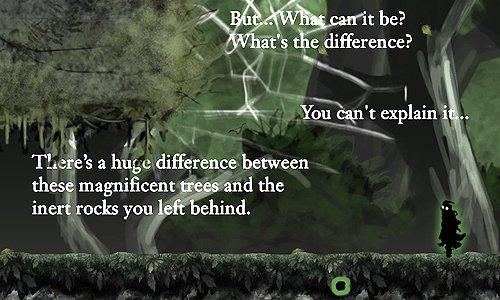

As Born passes through the various environments of the world – a snowy mountain peak, a dense forest, a volcanic lava field, even a derelict human city – he gains access to new powers that allow him to overcome the various Void beasts he encounters and solve puzzles. Being of the Void himself, Born knows next to nothing of emotions or feelings; in each area, he must find a special flower whose unique color is a brand new experience for him and awakens a new part of his consciousness. Thus, he gains new powers like running, jumping, and creating fire.

Combining powers is vital for both combat and puzzle-solving in Nihilumbra. Applying colors to a surface in the world works like painting with a brush, and operates completely independently of Born; while he is controlled via keyboard, the mouse handles his special abilities remotely. Paint a surface blue, for example, to allow Born to run across it, picking up speed for longer jumps. Spread red in the path of an enemy to burn them and clear a way for Born, who is otherwise unarmed. Born can, however, also interact with the environment himself by moving boxes and stepping on switches. To be successful, players will need to master a combination of both techniques.

Though it is typically a better option to avoid baddies altogether by stealthily sneaking around them or by using your abilities to make a hasty retreat, sometimes the only way past an enemy is to dispatch them. Born has neither an arsenal at his disposal nor pugilistic inclinations, and attempting the classic Plumber’s Stomp on any enemy in Nihilumbra equals instant death. Trickery is the name of the game here, and it is entirely possible to, for instance, use an enemy’s own momentum against him by sending him sliding into a pit or sticking him to a wall through the use of your abilities. Born does acquire a lethal “Fire” ability late in the game, but even this is limited to working only on certain foes and surfaces.

While most puzzles offer fairly simple and apparent solutions, it is the combination of platforming and special abilities that I found mildly frustrating. It felt counterintuitive to maneuver Born with one hand while the other was busy opening his ability menu to select the proper-colored ability for the situation at hand, then targeting the correct spot while moving to apply the color. This is a particularly big hassle during auto-scrolling stages, where one slight misclick can cause Born to be assimilated back into the Void, forcing constant restarts from the last checkpoint. I found some sections near-impossible using my laptop’s keyboard/trackpad combination; I highly recommend using an actual mouse. Abilities can be accessed using the number keys, as I later found out, but I happened upon this only through lucky coincidence, as there were no on-screen prompts or cues to press them at any point.

Accompanying Born on his journey is a narrator who observes the world and creates a personal connection with the protagonist in a game with no other dialog or characters. Similar to the 2011 RPG Bastion, Nihilumbra’s narrator gives meaningful insight and analyses on the way Born’s actions shape and affect the world around him, and how this, in turn, causes a change in Born himself. The narration makes Born’s journey a poignant one, extending it beyond a “get from point A to point B” chore. The juxtaposition of Born’s desire to be free of the Void with the wanton destruction left in his wake as it continues to nip at his heels, forced me to question the justness of Born continuing to plod ahead. Though the usually poetic script is delivered with serenity, a few awkward moments crop up as it occasionally switches from vocalizing Born’s stream of consciousness to providing omniscient bestiary descriptions of enemies.

Equally important as Nihilumbra’s narrative structure are its graphics, particularly its limited use of color. Each world has its own primary palette, with one dominant hue overshadowing all the others: shades of green in the forest, deep and malign reds in the volcanic landscape, etc. However, at the outset of Born’s journey, backgrounds resemble nothing so much as stylish gray-and-white pencil sketches. This often makes for a stark contrast between the monotone backgrounds and the bright splashes of color when using Born’s abilities. It isn’t until Born finds the first flower and gains his first ability that the world starts to slowly grow more vibrant. Thus, the game’s use of color reflects Born’s own journey toward becoming more human. As a 2D side-scroller with limited environmental features, what is on screen is either very basic terrain or indistinct, watercolor-esque backgrounds. This feels appropriate, however, given the game’s desolate mood. The Void monstrosities, on the other hand, come out of the “Giger Illustrating a Lovecraftian Children’s Book” file – grotesquely misshapen, filled with a blacklight luminescence.

The understated musical score further underlines Born’s isolation, as long, drawn-out strings and desolate themes will be your constant companion. Elsewhere, sound effects are common fare: swishes and spuds when landing a jump, crates splintering apart, enraged monsters screeching whenever they catch a glimpse of their prey.

Nihilumbra’s puzzle design remains fairly simple and focused throughout, with puzzles generally limited to a small area and not involving multiple steps or requiring overly complicated out-of-the-box thinking. Typically, Born either needs to manipulate an object in the environment or use an ability to accomplish some goal, though later stages frequently require combinations of various abilities. To activate a hard-to-reach pressure panel, for example, Born may need to cover a section of ground with his blue “Fast” ability and push a box onto it, causing it to quickly slide along until it settles on the pressure plate, opening the connected gate elsewhere.

The core game doesn’t offer much of a challenge, and can be finished in a single 2-3 hour sitting. However, completing the initial campaign unlocks special ‘Void’ stages – a chance for Born to go back through each of the levels, albeit redesigned with tougher enemies and more devious traps, and eradicate the last vestiges of the Void that had previously consumed the world while following him. This is a great idea, giving players the chance to see Born do something for the world he has grown to care about. Be prepared, however, for a breakneck learning curve: the new puzzles are extremely tricky and both enemy encounters and platforming suddenly require lightning reflexes and more than a few trial-and-error attempts.

I breezed through the main storyline, but couldn’t clear more than a smattering of the initial Void stages. They can, however, be tackled in any order and do not have to be played in sequence, so I could easily skip over tough stages and come back to them later on. Born has access to all of his acquired powers in this mode, but don’t expect much more in terms of plot development: Apart from your personal sense of accomplishment, there is no further narrative. In fact, the narrator – the game’s primary storyteller – is nowhere to be found in this mode.

Nihilumbra trailer

Nihilumbra features a touching message of redemption, but the story is meant to passively wash over you, providing no opportunity to interact with it in any way. This somewhat robs it of that vital spark that would have, ironically, made it come truly alive. But for those who don’t mind a more distant approach to their narrative, Nihilumbra is a competent, stylish puzzle-platformer that successfully punches through its few interface hang-ups.

Grimind

Fear, like any primal emotion, is difficult to instill into a captive audience. To feel uneasy and uncomfortable, much less afraid, while playing a video game requires more than a simple suspension of disbelief – it requires the sure and steady hand of a designer who’s tapped into what haunts the subconscious self. Pawel Mogila, designer of the physics-based horror platformer Grimind, reaches deep into his bag of tricks to makes us squirm in our seats, generally to favorable effect. What I felt while playing could be classified more as “intense nervousness” than “outright horror”, but Grimind made me seek out its well-lit areas more than once, afraid to venture beyond their protective cones of radiance.

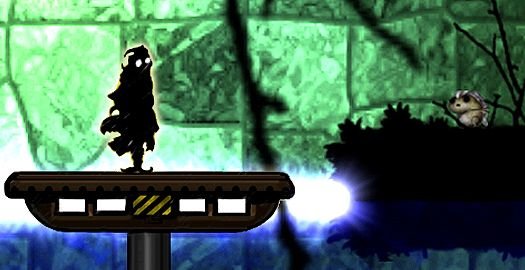

To venture into Grimind is to take control of a short and stubby, porcupine-like, shade-wearing creature who awakens to find himself deep within a dense system of seemingly subterranean tunnels and chambers. He is all alone, save for the slithering, slimy, squishing noises caused by something hiding in the darkness, and the growling whispers of whatever unfriendly creatures lurk just on the edge of vision. Unarmed, unprepared, and without any knowledge of where you are, your task is to find the hospitable light of the surface again…or else die trying.

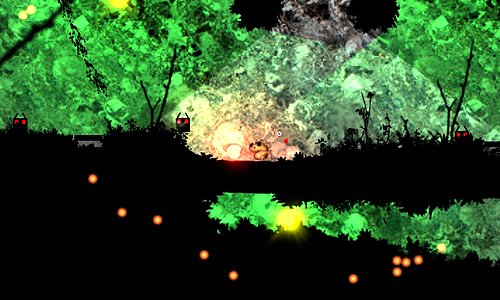

Grimind is packed full of movement-based puzzles; you’re constantly on the hunt for the next lever, switch, or platform that will move or operate something within the environment. This can be quite tricky at times, as your vision is limited, as befits an underground cavern. Most of the time, the majority of the screen is bathed in utter blackness, with only sections of muted illumination highlighting your general vicinity. Locales vary from wide-open cavernous rooms to narrow tunnels with barely enough clearance to walk through.

Backgrounds are tinted in warm, earthen colors: brownish reds, deep purples and darkest blues and greens abound. The only other light sources are glowing orbs set into the tunnel walls at intervals, making you strain your eyes to catch a peek of what lies all around you. The color palette is visually pleasing and literally easy on the eyes, but it leads to one of the game’s biggest challenges: hunting for levers and switches to manipulate the world around you sometimes becomes little more than a crapshoot when you can’t distinguish said lever from the black foliage surrounding and concealing it. Passages can be likewise camouflaged, making it necessary to cover every inch of ground and jump into walls on the off chance that you missed a critical mechanism – not the kind of “exploration” adventure games are typically known for.

The lack of visibility can be easily excused; one only needs to consider the mood Grimind is aiming for to overlook a few dark corners in the game. A different, albeit minor, issue arose from the game’s controls. You move your character using the W, A, and D buttons, with the S used for a few underwater diving sections. (Gamepads are also supported.) Moving the on-screen mouse cursor swings the camera in the indicated direction, and pressing the left and right mouse buttons causes you to grab and throw objects, respectively. It sounds basic, yet there were two key moments in the game that left me absolutely nonplussed for lack of knowing how to get around an obstacle. This wasn’t due to an especially devious puzzle, but rather to insufficient cues for how to get my character to perform a required action.

Grimind gameplay demo

Throwing items in a desired direction, as it turns out, has absolutely nothing to do with which way you’re facing or your location, and everything to do with where the mouse cursor is in relation to you. At all times, your character (I’ve taken to calling him Grimind) will throw objects in an arc following the on-screen cursor, which was left for me to discover on my own and caused me to get hung up on a couple of puzzles. The same is true late in the game, where the placement of the cursor directs a group of creatures following your commands. While seeming like a simple gripe that would have been (and was) easy to figure out on my own, it would have been even easier to include directions or at least a visual cue to avoid this blunder.

Where the wonderfully creepy soundscape (a score is nonexistent; instead you’ll be listening to atmospheric background noise) set me on a nervous edge, it was Grimind’s utter vulnerability that amplified the scares, turning even a minor enemy encounter into a potentially lethal showdown. Grimind’s sole adversaries, for much of the game, are little red-eyed devilish imps or sprites, which chitter away in the shadows, then suddenly and without warning, amid cacophonous barks and bellows, throw themselves en masse at you. Typically, your only hope for survival lies in running, though by the time you see the hordes descending on you it’s usually too late already. Your only means of fighting back: the little buggers detest bright light – luring them near a strong light source will instantly deteriorate them into nothingness. Of course, strong light sources are few and far between in this subterranean kingdom. Even the rare times when Grimind has a portable light source to help him survive are little better, as he is usually greatly outnumbered, and even just a few hits will swiftly end his life.

Luckily, automatic checkpoints are spread liberally throughout the game’s fifteen chapters, never starting you back too far from where you died. Likewise, there is no limit to the number of lives you have. Once a chapter has been reached in the campaign, it is then possible to replay it at any time directly from the main menu, offering you a chance to find and uncover the secret area, one of which is hidden within each chapter.

Platforming itself is kept at a manageable difficulty. The usual pitfalls (pun wholeheartedly intended) like bottomless pits, disappearing or crumbling floors, scrolling or timed stages, and the like – generally used to jack up the level of intensity of platforming – are largely absent here. Instead, the platforming takes a back seat, serving more as a means of moving between puzzle-solving sections. The most challenging moments you’re likely to encounter involve jumping between vines, timing it to take advantage of their swinging momentum to carry you further, and maneuvering an airborne platform through corridors lined on top and bottom with deadly spikes. This is perhaps why the game’s boss – the only boss in the entire game – is disproportionately more challenging than what came before, since he requires staying airborne by climbing and jumping from vines as both a mechanism of defense and a means to attack.

Any issues caused by its cluttered visibility fit the game’s mood and are easily overlooked. Minor complaints about unclear controls are likewise quickly forgiven. I did, however, take more issue with what I perceived to be an ambiguous ending to the story, sketchy and paper-thin as it was. Having bested all puzzles and made my way through one area after another in order to return to the surface world, and after vanquishing the end boss I was no closer to understanding his motivations and goals – or even who or what he was. Even the one or two plot twists along the way fail to receive any kind of payoff, making the whole narrative seem like a bit of an afterthought. Worse yet, completing the game fails to answer any of the tantalizing questions posed by the game’s trailer: Who am I? How did I get here? For that matter, where is ‘here’?

Grimind trailer

Playing at a rather leisurely pace – and having gotten considerably stuck once or twice along the way – my game time clocked in at somewhere just upward of five hours. That’s no small time investment for such an ambiguous finale. So rather than expecting Grimind to pay off once you reach the end, instead take it as a complete package from beginning to end. The narrative offers little in the way of incentive to get going or reward for reaching its conclusion, but it does provide plenty of wondrous moments along the treacherous, dimly lit way.