Review for Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs page 2

Game information

Adventure Gamers Awards

A Machine For Pigs.

What a perfect title. Four simple words that communicate an uncanny amount of unease and discomfort. When I first heard the announcement for the upcoming sequel to Amnesia: The Dark Descent, I immediately shivered and felt unclean. What did it imply? Literal pigs? Pigs as a metaphor for humanity? A slaughterhouse? Some other kind of bizarre device? A machine that used pigs? A machine that pigs used? All potential answers, all equally unsettling.

Ugh. A machine for pigs. Ew.

Well, the game itself is now here, and if the title made me feel gross, the game made me want to take a three-hour shower. And in a series as deliberately masochistic as this, that is high praise indeed.

Even though 2010’s Amnesia was essentially a variation on the formula Frictional Games established with their earlier Penumbra series, it felt significantly richer and more successful at creating the tension and dread that mark great horror games. For my money it is the best horror game ever made. While it had its flaws, the game managed to create a sense of utter helplessness and oppression unmatched by its peers (except for, perhaps, the venerable early Silent Hill games). While it followed a familiar survival horror structure, it removed combat from the equation, leaving the player with only two options when faced with the abominations contained within its castle: run or hide. There were other innovations, but this was Amnesia’s most radical departure from previous horror games, where you could almost always count on blasting away the zombies, ghosts, or dinosaurs with a pistol or shotgun.

For the follow-up, Frictional Games joined forces with thechineseroom, developer of the experimental first-person looker Dear Esther as well as the alternately brilliant and frustrating Half-Life 2 horror mod Korsakovia (which, if you love horror games, is absolutely worth some of the headache). The partnership was a smart move, as thechineseroom’s experimental pedigree meshes perfectly with Frictional’s design savvy, bringing a more cohesive, literary vision to Amnesia’s house of horrors.

A Machine for Pigs is not a direct sequel. In interviews, Creative Director for thechineseroom, Dan Pinchbeck, warned players to think of the game as more of a side story than a full sequel, and I would have to agree. The game is short (though priced accordingly) and has only the most tenuous of connections to the previous Amnesia. Other than a couple of brief name drops, A Machine for Pigs is an entirely original tale.

You play as Oswald Mandus, proprieter of the largest food processing plant in London. Judging by the dates on the letters you find, it is late 1899. You awake in your mansion to find your memory spotty (hey, amnesia, imagine that!) and your two sons missing. After a cryptic conversation with a foreboding gentleman on a telephone, you discover that your children have been trapped within the factory by an unknown saboteur who is attempting to bring down the business. So of course it’s your job to descend into the depths of the facility and rescue them. Yay!

The game starts out retreading well-worn ground: exploring an empty mansion with the occasional spooky noise, ghostly apparitions, and strange notes. It’s well-made but familiar. You spent much of the first game doing precisely this in strikingly similar environments. At first I was concerned – was this simply going to be more of the same? In retrospect, however, this seems to be intentional, a way of connecting the games visually and mechanically. Before long, you’ve moved beyond the mansion and into the factory, where A Machine For Pigs comes into its own. It’s clear early on that the factory isn’t just a factory. There’s something else going on in the stinking depths of the Mandus Meat Processing Plant—this is obviously no ordinary slaughterhouse, and what are those things you see scurrying in the distance? They sounded like pigs, but… creepier?

At this point some of you are invariably thinking: get to the point, man, is it scary? It’s true that there is often only one criterion that matters when rating a horror game, and that is: did you need to sleep with a nightlight afterward? With A Machine For Pigs, however, the answer is complicated and depends on where you’re coming from and what you want out of a game like this. To be blunt, it’s not as scary as the first Amnesia. In terms of sheer bowel-straining terror, it’s just not on the same level. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, by the way. The changes made have simply de-emphasized the stealth/avoidance sections in favor of more exploration and storytelling. I could only play The Dark Descent in 30-45 minute sessions before my nerves were so frayed that I needed to call it a night. By comparison, I played through Machine in two extended sessions, drawn forward by morbid curiosity to see just how wrong this game could get.

And it gets very, very wrong. The plot is a huge step up from the first game. For one thing, I can already tell that in a few weeks I’ll actually remember it. First, though, the flaws: there are a few tiers to the narrative and they don’t all work. The immediate plot of the game — wherein Mandus tries to find his children who (tell me if you’ve heard this one before) appear as ghostly apparitions whispering things like “Daddy, daddy, come and play with us”— is often nonsensical, clichéd, and unbelievable. The game springs a twist halfway through that is utterly pointless, and in general this part of the story is muddled and weak. Fortunately, this underwhelming premise mostly serves to support a much, much more interesting backstory that must be pieced together through notes, scraps of dialogue, and the environment. It’s not unlike Dear Esther, where the gameplay is set up as little more than a walking tour of a dark and fragmented narrative that needs to be pieced together through exploration and thought. It also happens to feature a lot of theatrically intense voiceover work by a man with a gentlemanly English accent, which does much to further the comparison.

The backstory concerns the founding of the company, the tribulations that Mandus has endured, and the obsession that ends up transforming the nature of his work into something far more disturbing than processing meat. These elements are fantastically well-realized. The notes you find, from Mandus and others, are written with an ear for period vernacular and poetry. The story they uncover is haunting, horrifying, and fascinating. Themes of industrialization, radical politics, ambition, and sacrifice are run through the grinder, and the resulting sausage is not pretty.

The previous game often threw large open settings at you, with multiple enemies stalking the area, forcing you to creep around, hide in closets, and constantly weigh the pros and cons of being in the light. Light helped maintain your sanity, but it also made you visible to the monsters. Darkness drew you towards madness, but helped you hide. It was a brilliant lose-lose situation, and the tension between survival and madness underpinned the entire game. Here the focus has been shifted toward the environment-based narrative, and the gameplay has been streamlined accordingly, for better or worse. You spend less time thinking about the game mechanics and more time about the world itself. Most prominently, the sequel dispenses with its predecessor's insanity system entirely. While at times the original system felt overly “game-y”, often forcing you to go stare at a wall for 20-30 seconds to regain your composure, it added an additional fragility to your character and, most importantly, prevented you from looking at the enemies for more than a split-second, keeping them shrouded in mystery and making them all the more terrifying. The enemies in A Machine for Pigs remain scary, but lose some of their impact since their mere presence nearby isn’t a danger to you.

As in The Dark Descent, you cannot fight your opponents. This means that avoidance is again your only option. The stealth mechanics are simple: hide behind something, preferably in a dark place, and enemies can’t see you. That’s really all there is to it. Foes have a short line of sight and iffy hearing, meaning most of the time you’ll be able to squat behind a crate a foot away and they’ll walk right by. In streamlining the gameplay, the developers have also made it easier. That said, the enemies are disturbing enough in their design that they’ll still creep you out even if you’re not actively afraid of being caught. And believe me, if you do ever get caught, your heart will be pounding. The stealth is both easier and weaker than in the first game, but it has been consigned to a smaller portion of the overall game, rather than being the core gameplay mechanic. I’m sad to see it go, but surprisingly it doesn’t hurt the game as much as one might expect.

In addition, the ability to light and extinguish light sources using flint has been removed here. This means that your lantern is your only option for illuminating an area, and you no longer have a limited supply of lantern oil. This lack of resource scarcity tempers some frustration but takes away another way for the game to heap on the dread. You’ll no longer find yourself running low on oil in a dungeon with three unknown abominations between you and the exit. It’s not really better or worse, it’s just different.

Puzzles are simple but nicely designed, as in the first game, relying less on lateral thinking and more on environmental awareness. Most involve finding an item somewhere else in the level and taking it back to an earlier spot where it was needed. A truck that is blocking your path can be moved by retracing your steps to find a way to refuel it, for example. Simple, but not immediately obvious. As in The Dark Descent, the puzzles here serve to increase immersion rather than stand out as arbitrary obstacles placed by a designer.

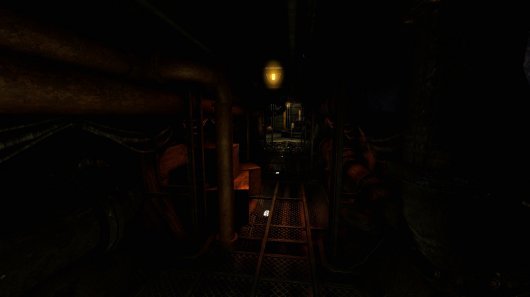

The meat processing plant is the game’s most prominent environment, its most interesting character, and its shining achievement. Part functional slaughterhouse, part arcane temple to industrialism, the underground factory is the physical, architectural equivalent of a Nine Inch Nails album: scraping metal, churning pistons, troughs of grit and gristle, all drenched with rust and blood. It starts off bad and gets worse the further you descend. The design of the place is remarkable – I can think of few other environments in gaming that felt so overwhelming and oppressive.

The factory looks great, which is to say, it looks absolutely awful, as do the game’s few other environments. Technically, Frictional’s in-house engine seems to be unchanged since the previous release: competent and impressive for such a small team with limited resources, but hardly mind-blowing, especially after three years. Textures are muddy, performance occasionally hitches, and character models are best viewed from a distance, in the dark, from behind a crate. But it’s hard to complain when everything conveys such a tangible sense of foreboding. Everything looks grim and metallic and riddled with tetanus or worse, and the layout of the factory has an awful beauty, like a German Expressionist painting.

It’s varied as well. The artists have gotten a lot of mileage out of the setting, despite nearly every area being a variation on turn-of-the-20th-century brass, iron, and stone with muddy brown and gold steampunk-ish machinery lining the walls. Yet each area is a distinct shade of awful: from austere managerial offices to piston rooms with seemingly infinite expanses of darkness to claustrophobic laboratories. One of the keys to this is that each section is clearly given a purpose within the factory – this provides the power, that is where the product is treated for disease, here is research and development, there is – well, the less said about there, the better. The design strikes a subtle balance between “real, functional place” and “impossible hell maze.”

And the sound... God, the sound. Three years ago we graced the first Amnesia with a Sound Design Aggie Award and that quality has been soundly trumped here (pun not intended). Squeals, scrapes, whines, crunches, splashes, drips, breaks, grinds, and other unpleasantness are all rendered convincingly. This is a game that demands to be played at a high volume on a good pair of headphones. The music, by Dear Esther composer Jessica Curry, is another highlight. Haunting classical tunes play over scratchy, reverberating phonographs (you see, classical music was found to “soothe the product”). Dissonant blasts of brass erupt from silence, wailing like lost souls, while wistful piano underscores moments of sad revelation. And then there are the moments when the roar of the machine drowns out nearly all other sound, leaving you suffocating in white noise, blind to whatever is around the next corner.

All of this—the frantic narrator ranting about the filth of the world, the endless and nihilistic sprawl of the factory, the sound design that overwhelms—combine to disturb more deeply than any throwaway jump scare. The game has those too, but what you’ll take away is the darkness, the grime, and the desperation. This is a short game, playable in four or five hours—less if you rush—but the impression it leaves is lasting. I’ve played plenty of games that have things leap out of the shadows at you. I love that, but I’ve been there. What I want these days are games that make me think and feel. And Amnesia: A Machine For Pigs does both! It’s a win-win. Or is it lose-lose? I swear I’ll never look at a pig the same way again.

_capsule_fog__medium.png)