Adventure Architect #2: Chivalry is Not Dead, Part 2

The way in which I like to approach the adventure game is as an interactive story; as such, the very first thing I focus on when creating a game is the story it will tell. But I feel that it isn't enough to make up a story solely for the sake of justifying the gameplay that emerges from it. While doing so in and of itself is certainly a lofty goal to strive for, it does tend to make for a shallow and formulaic end product. For a story to truly stand out as a meaningful work of art, it must convey a purpose and make some sort of statement about the world. Hence, this next article in the series will focus on the process of coming up with such a story.

A recurring question that I hear being asked of storytellers of all mediums is "Where do you get your ideas?" Obviously, I can't speak for all storytellers, but in my case, the answer is "everywhere". It doesn't matter whether I'm watching cartoons or watching random strangers on the street; in the end, every interesting thing I observe is fair game for contributing to the swirling miasma of inspiration located inside my head.

I've noticed that when writing a story, some people like to begin by developing a setting, whereas others prefer to focus on creating characters. While I acknowledge that both are important, I tend more towards the latter category, considering that the stories I find most interesting are usually the ones with complex and memorable characters. After all, no matter where and when a story takes place, its characters, when done well, have a human quality to them that allows us to empathize with their situations and relate them to our own lives.

I've noticed that when writing a story, some people like to begin by developing a setting, whereas others prefer to focus on creating characters. While I acknowledge that both are important, I tend more towards the latter category, considering that the stories I find most interesting are usually the ones with complex and memorable characters. After all, no matter where and when a story takes place, its characters, when done well, have a human quality to them that allows us to empathize with their situations and relate them to our own lives.

In the case of Chivalry, the ideas for characters stemmed from various epic fantasy novels I read throughout my teenage years. While I found such stories entertaining and enthralling in and of themselves, one thing that always bothered me was how in many cases, every character would fit neatly into a pre-defined archetype: the hero, the villain, the love interest, the wizened mentor, and so on. And complementary to such archetypes came clearly-defined categories of "good" and "evil", with little room for the hazy shades of grey one tends to see in real-world interactions with others.

As a result, one day I started thinking to myself: what if I took these archetypes and twisted them around somehow, in an attempt to illustrate the absurdity of such a black-and-white view of ethics? Why don't I turn the hero into an arrogant, deluded fool of nothing more than average talent, and the villain into someone who ultimately turns out to be harmless? Furthermore, why don't I have the true protagonist of the game -- in other words, the character that the player controls -- be the villain's henchman, an archetype that traditionally plays only a minor role in your typical fantasy story?

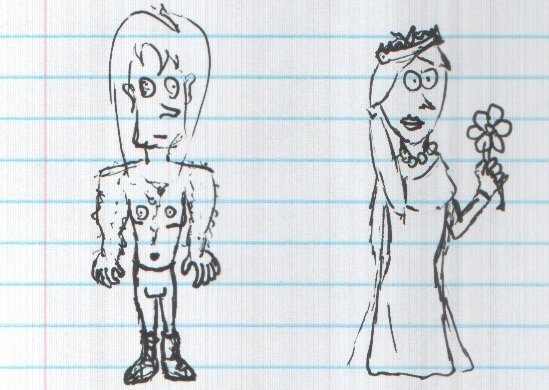

Several brainstorms, long walks, and caffeinated beverages later, these ponderances began to shape their way into some semblance of a plot. Right around the point that this happens is when I usually start to write things down concretely in a design document of sorts. I say "of sorts" because I don't follow any specific format when creating my documentation; in fact, in past projects of mine, much of the documentation consisted of pencil sketches and messy handwritten notes in point form. In this case, however, I decided to create a nice, clean Word document divided into two sections: one describing the major characters in the game, and one summarizing how the plot will progress, including every scene that the player will be visiting.

Here's a snippet from the first section:

Here's a snippet from the first section:

Phlegmwad -- This is you. Extremely ugly to the point that you must wear a paper bag over your head at all times, everyone hates you and thinks of you as a disgusting little creep. You make your living as Lord Horrible's personal assassin, mainly because you're pretty good with a dagger and no one else in their right mind would ever hire you.

And here's one from the second section:

1) Lord Horrible's Lair -- Lord Horrible briefs you on the task at hand: kill the Queen so that he can usurp the throne as ruler of Everything. You accept.

2) Castle Balcony -- The Queen is standing here, contemplating life. Whatever you try to do to her, she will recognize you and offer to free you from the clutches of Lord Horrible forever. From here, you have a couple of options:

You could ignore her offer and kill her. Lord Horrible will then rule over Everything, and the game will end.

You could accept her offer. She will tell you of a prophecy she found in which a farm boy named Leslie from Badger's Fields is fated to defeat Lord Horrible using the Sword of All That is Good...

The document in its entirety is a mere three pages long, which, compared to most design documents (or so I hear), is rather short -- I'm intentionally leaving out such details as dialogue, puzzle solutions, and interactive items. The reason for this is simply because at this point in time, I don't need to include them. Traditionally, when games are created as part of a team, and every person is in charge of one specific part of production, it makes sense for a designer to create a document detailing every single thing that must go into the game. However, since my approach is more holistic, bearing more similarity to other solo creative endeavours (e.g. writing a novel or a comic book) than to team game development, I'm allowed more leeway to keep some of these finer details in my head, and to make some of them up as I go along. A brief outline like the one I've created brings about enough of a balance to make such leeway possible, while at the same time keeping me on track so that I have an actual ending to work toward.

The document in its entirety is a mere three pages long, which, compared to most design documents (or so I hear), is rather short -- I'm intentionally leaving out such details as dialogue, puzzle solutions, and interactive items. The reason for this is simply because at this point in time, I don't need to include them. Traditionally, when games are created as part of a team, and every person is in charge of one specific part of production, it makes sense for a designer to create a document detailing every single thing that must go into the game. However, since my approach is more holistic, bearing more similarity to other solo creative endeavours (e.g. writing a novel or a comic book) than to team game development, I'm allowed more leeway to keep some of these finer details in my head, and to make some of them up as I go along. A brief outline like the one I've created brings about enough of a balance to make such leeway possible, while at the same time keeping me on track so that I have an actual ending to work toward.

Thus, I now have a purpose and goal to strive for in my storytelling, and an outline that forms its skeleton. Next time, I'll discuss the process of putting meat on these metaphorical bones; that is, adding various forms of interactivity in ways that complement the story.