Adventure Architect: Part Four

The pre-production phase—puzzles, locations, and concept art

A few months ago, I set out to create an adventure game from the ground up with three important features: an engrossing storyline, a good dose of humor, and the right mix of challenging but enjoyable puzzles. I wanted to make a game that weighed in heavily on the fun factor scale, and also had the professional-quality production values to back it up. I knew it would be fun, and I knew it would be a lot of work. What I didn't know was just how much fun—or how much work—that would be.

But now here I am, a few months in and finally I'm ready to begin adding new layers to the story outline. This is where the game's production paths start to diverge. With the basic storyline and backstory firmly in hand, I can start to work on the "details phase" in which I hammer out everything there is to know about each game location, each character relationship, each puzzle—and how they all fit together. And I can also begin serious work on the visual design phase, which involves everything from animating character sprites to drawing and coloring each room background.

But before I branch off in those directions, I'd like to take a step back and bring into focus the visual aspects of the pre-production phase. As I was working on the storyline, I also spent some time trying to visualize the different ideas that came from those brainstorming sessions. This was helpful because it got me thinking visually—something very important in a graphic adventure—and it also became a two-way street where ideas from the storyline were influencing the puzzles, and ideas from the puzzles began to cry out for inclusion in the storyline. (Case in point, as I'll illustrate later, is a desert location called Vulture Rock.)

So here, then, is a transcript of what I jotted down in my design notebook, followed by a glimpse into the pre-production visuals that sprang from it.

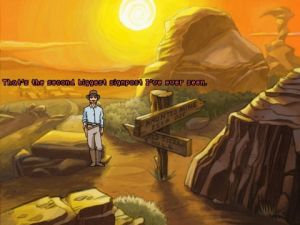

In a dusty red rock desert, you come across a rock formation protruding into the sky like a tall, thin cone, with a horizontal "beak-like" outcropping at the very tip. This is Vulture Rock, and it's dotted with nests along the surface. There also appears to be a long and very precarious-looking trail that winds back and forth (and on off the screen, perhaps) up to the top. At the very tip, where the "beak" juts out, there's a nest all the way at the end. Walking to it would be fatal, though, because it would snap and fall under your weight. This is unfortunate because, of course, you need to retrieve something from the nest.

The idea for Vulture Rock came to me after I wrote the words "strange rock formation" in one of my early brainstorming sessions. It stuck with me because I thought that, visually, it would be a pretty cool place for the hero to have to visit and navigate, and it seemed to make sense in a desert context. It's also full of puzzle possibilities.

Notice, though, that at this point all I've done is suggest an obstacle—you need to get something in the nest, which is dangerously out of reach—but I didn't pose any solutions. That's become one of my key design strategies. This phase of the game development is about creating obstacles for the hero; in the next phase I'll start to fill in the solutions. I have a few ideas about how to solve the puzzle, but I try to keep those thoughts separate until I've established every in-game location and obstacle throughout the game, or at least throughout a particular game area.

Then I'll begin to look at different ways to relate locations and items to each other, and in turn to relate multiple layers of different puzzles to each other, so that I can increase or decrease the level of complexity for each puzzle based on the needs to the story at that particular point. I don't want to rely on inventory-based puzzles at every turn, and this seems to be a good way of keeping a number of possibilities on the table.

On to the next conceptual element: a Wild West jail cell that also stems from a few words I'd jotted down earlier. In fact, initially I'd even thought about starting the game with the hero having to escape from a jail cell, but in the end I couldn't make it work in the context of the story. Instead I filed the idea away, and found a natural place for it later in the game after I'd fleshed out the who, what, and where surrounding the treasure's backstory.

You're in a typical Old West jail cell in a typical Old West town. Unfortunately, you get to see the cell from the inside. There's a barred window set into the crumbling side wall of the cell overlooking a back alley, and beneath the window lies a slumped-over skeleton with one arm clearly outstretched and visible. The rest of the sheriff's office is visible on the other side of the bars, and through them you can see a desk, bookshelves, a bottle of moonshine, and a longhorn skull strung up on the wall. A deputy sheriff paces back and forth across the room nervously, glaring at you as he moves.

Here I didn't focus as much on the problem because it's self-evident: the hero is locked up and needs to find a way to escape. I've always liked these kinds of closed room puzzles because it's clear that the game is going to supply you with everything you need to piece together an escape—if you can figure out what you're supposed to do. I envision this as a complex (but fairly intuitive) puzzle that will force the player to give it serious consideration before completing it.

That's all I've got for this time. Next month, I'll move away from this preliminary concept work and into the early phases of actual game production.

Next: Forming a design team, and storyboarding the game one location at a time